For prostate cancer patients, hormone-blocking therapies have long been hailed as life-savers. However, recent research suggests that a certain hormonal therapy called androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) may increase the risk of dementia. What happens when the very therapies meant to keep cancer at bay also raise questions about cognitive health?

Prostate cancer affects about one in eight men in their lifetime, and nearly half of these patients receive ADT at some stage. Pioneered by surgeon Dr Charles Huggins (1901-1997) in 1941, ADT has since become a cornerstone of prostate cancer therapy. In recognition of his work, Dr Huggins was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1966.

ADT is a form of hormonal therapy that lowers the levels of androgens – male sex hormones such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). From early development, these hormones stimulate the growth and activity of prostate cells by binding to androgen receptors on their cell surface. Most prostate cancer cells retain this hormonal dependency, continuing to rely on androgens for their growth and survival. By depriving the body of androgens, ADT effectively ‘starve’ prostate cancer cells, thereby slowing disease progression.

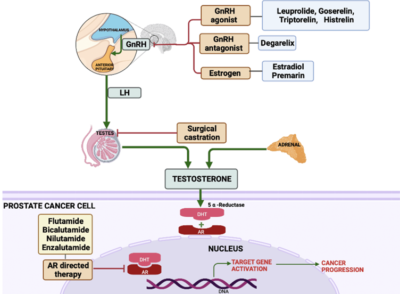

ADT comes in several forms (Figure 1); each designed to inhibit androgens in some way:

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist: Reduces testosterone production in the testes by causing an initial temporary increase (a ‘flare’) before achieving a sustained drop in testosterone levels as the body adjusts.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist: Lowers testosterone production in the testes by directly blocking luteinising hormone, leading to an immediate reduction.

- Androgen receptor-targeted therapy: Blocks androgen receptors on prostate cancer cells, preventing androgens from stimulating cancer growth.

- Oestrogen therapy: Suppresses luteinising hormone production to reduce testosterone levels, but it is less commonly used today due to cardiovascular side effects.

- Orchiectomy: A surgical removal of the testes to induce a permanent and immediate reduction in testosterone levels.

Figure 1. Sites of action of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) on testosterone production, regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Abbreviations/acronyms: AR, androgen receptor; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone. Source: Kakarla et al. (2022), Cureus.

However, ADT is not a definite cure for prostate cancer because the cancer can become resistant after a few years, leading to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Prostate cancer cells can evolve ways to grow without androgen signalling. They may produce their own androgens or activate androgen receptors without external hormones. At this stage, other treatments like chemotherapy and immunotherapy become necessary to manage the cancer.

Despite that, ADT remains a vital tool in prostate cancer therapy. By slowing cancer growth and reducing symptoms, ADT can provide months or even years of disease control. This is particularly important for patients with advanced or metastatic cancer, where options for a cure are limited or not existing. Additionally, ADT can enhance the effectiveness of other cancer therapies, making it a valuable part of combination therapy in high-risk patients.

Medical interventions carry risks, especially in oncology, where treating cancer often requires toxic agents. Similarly, ADT can bring various side effects due to the drop in testosterone. Short-term effects include hot flashes, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, mood swings and fatigue. Some patients may also experience breast tissue growth (gynecomastia). Long-term effects of ADT include loss of bone density, muscle loss and weight gain, which may lead to osteoporosis, insulin resistance and increased cardiovascular risk.

Growing evidence, however, is linking long-term use of ADT with an elevated risk of dementia, a neurodegenerative disease marked by progressive memory loss. A 2024 meta-analysis of 17 cohort studies found that prostate cancer patients treated with ADT had a 20-26% higher risk of dementia compared to those who did not receive ADT. This risk rose up to 40% for those on androgen receptor-targeted therapy and those who underwent orchiectomy. A meta-analysis is considered top-tier clinical evidence because it pools data from all relevant studies to draw a consensus result. It is also estimated that 25-50% of prostate cancer patients undergoing ADT experience some level of cognitive decline.

Now, why is ADT linked to dementia or cognitive decline? Current evidence suggests that testosterone plays a protective role in brain health in three major ways:

- Amyloid Beta (Aβ) Degradation: Testosterone activates a protein called neprilysin, which helps degrade Aβ peptides in the brain. When testosterone levels drop due to ADT, neprilysin activity decreases, leading to a buildup of neurotoxic Aβ plaques. This process impairs communication between neurons and triggers inflammation, resulting in neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

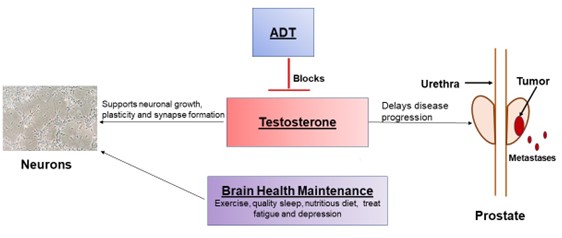

- Hippocampus Support: Testosterone converts to a form of oestrogen in the brain, which binds to hippocampal receptors to promote neuronal growth and synaptic plasticity (Figure 2). As the hippocampus is essential for memory formation, it is one of the earliest brain regions to degenerate in dementia. When testosterone is lowered by ADT, this neuroprotective support in the hippocampus also declines.

- Anti-inflammation: Testosterone can bind to androgen receptors on immune cells to reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Testosterone also increases the production of IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine. Therefore, as testosterone levels decline from ADT, it also disrupts the pro- and anti-inflammatory balance in the brain.

Figure 2. The impact of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) on prostate cancer and brain health. ADT reduces testosterone levels to slow prostate cancer progression, but it also weakens the natural neuroprotective effects of testosterone. Source: Reiss et al. (2022), Urology Today.

Given the wide-ranging impact of ADT beyond cancer control, additional interventions are often necessary to manage long-term health. For instance, physicians may prescribe medications like bisphosphonates or denosumab to counteract bone density loss. Regular exercise is also recommended to reduce bone and muscle loss, support weight management and improve insulin sensitivity. However, managing sexual side effects, particularly loss of libido, remains challenging since medications like Viagra address erectile dysfunction but not sexual desire.

Likewise, therapeutic options to combat cognitive decline linked to ADT are limited, making this an area of concern. Nonetheless, incorporating certain neuroprotective strategies may help minimise the cognitive side effects of ADT. Patients may benefit from regular mental exercises, cognitive therapy and lifestyle adjustments that support brain health, such as a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids and plant-based nutrients. Some evidence suggests that nootropic supplements (e.g., ginseng and ginkgo biloba) could also support cognitive function.

At Integrative Cancer Care, we provide various complementary therapies to support the health and well-being of cancer patients in their journey, especially as they undergo intense cancer therapies, whether chemotherapy, surgery or hormonal therapy like ADT. Our approach customises treatments to each patient’s unique condition, using an array of phytotherapy (phyto- means plant) protocols that include neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory compounds:

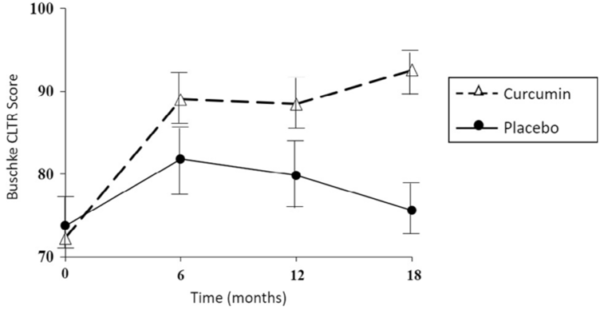

- Curcumin (in Curcumin combi and ProstaSol): A 2018 clinical trial showed that curcumin improved cognitive test scores and reduced brain content of amyloid among older adults compared to placebo over 18 months (Figure 3). In a 2024 meta-analysis of over 50 studies on chronic inflammatory conditions, curcumin was effective in lowering the levels of pro-inflammatory C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-α and IL-6.

- Ginseng (in IMUSAN and ProstaSol): A 2008 clinical study showed that dementia patients treated with ginseng for 12 weeks had improved cognitive performance compared to the control group. However, cognitive scores declined after ginseng was discontinued, suggesting that ongoing intake may be needed for sustained benefits. Ginseng also acts as a potent immunomodulator, offering protection against multiple autoimmune and inflammatory conditions.

- Quercetin (in ProstaSol): A 2023 cohort study followed a group of older adults for up to 14 years and observed that those whose diets are rich in quercetin were more resilient to cognitive decline. Food items high in quercetin include apples, berries, onions and kale. The anti-inflammatory capacity of quercetin is also well-established, with documented abilities to inhibit enzymes involved in generating pro-inflammatory molecules.

While ADT remains a cornerstone of prostate cancer therapy, recent findings are highlighting the impact of ADT on dementia risk. For patients facing the dual challenge of managing cancer and the side effects of therapy, integrative approaches offer valuable support. By incorporating phytotherapy compounds with neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties, patients can mitigate the cognitive and dementia risks of ADT (and even other intensive therapies like chemotherapy). Though research is ongoing, these complementary strategies offer a proactive and empowering path for patients to preserve their quality of life and cognitive resilience.

Figure 3. Effects of curcumin on verbal memory, as measured by consistent long-term recall (Buschke CTLR). After 18 months of treatment, the curcumin group demonstrated a significant improvement in verbal memory performance by about 20% compared to the placebo group. Source: Small et al. (2018), The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.