Colorectal cancer is not supposed to be a young person’s disease. Yet doctors are now seeing patients under 50 – otherwise healthy, often with no family history – facing a diagnosis we still associate with retirement age. In the U.S., it has become the leading cause of cancer death in men under 50, and the second for women in the same age group. In England, incidence is rising by over 3% each year in adults too young to qualify for screening. Similar patterns are emerging across Asia, Oceania and Europe. Something has changed within recent generations, and new evidence suggests the answer may lie in an unexpected place: the bacteria that colonised our gut microbiota in childhood.

The Global Rise in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer

The most comprehensive analysis to date of colorectal cancer in younger adults, typically between ages 25 and 49, comes from a recent study published in The Lancet Oncology. In this study, cancer epidemiologists from the American Cancer Society analysed data from high-quality registries across 50 countries to understand how colorectal cancer is shifting globally. The findings are unsettling: while incidence in older adults has plateaued or declined in many countries, cases in younger adults are climbing across much of the world.

In the most recent period analysed (2013–2017), the highest rates of early-onset colorectal cancer were reported in Australia, the U.S., New Zealand and South Korea, with incidence rates of 14 to 17 cases per 100,000 people per year. However, the trend matters more than the absolute numbers: in 27 of the 50 countries studied, incidence in younger adults has risen over the past decade. The steepest annual percentage rise was seen in New Zealand (+3.97%), Chile (+3.96%), U.S. Puerto Rico (+3.81%), England (+3.59%), Norway (+3.52%) and Australia (+3.01%). In many of these regions, trends among older adults were flat or falling – largely thanks to widespread screening programs that detect and remove precancerous growths – indicating that the rise in colorectal cancer is limited to younger age groups.

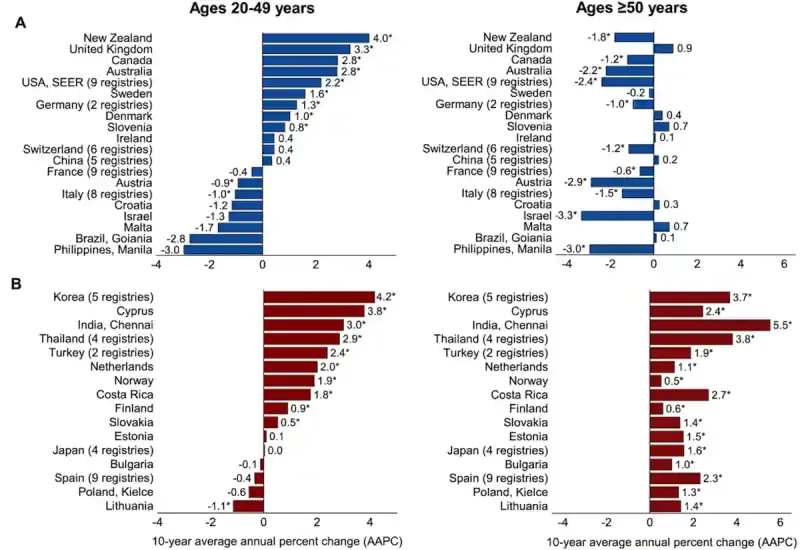

These findings are consistent with an earlier global analysis published in 2019, which examined colorectal cancer incidence across 36 countries from the mid-1990s to the early 2010s. The study reported rising rates among younger adults in 19 countries. Interestingly, the most striking pattern was seen in high-income nations (i.e., Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, Slovenia, Sweden, Denmark, the U.K. and the U.S.), where increases were confined to younger adults, while incidence in older adults declined or remained stable (Figure 1). In other countries such as Cyprus, the Netherlands, and Norway, the rise in young adults is occurring at roughly twice the pace observed in older populations.

Figure 1. Trends in colorectal cancer among younger and older adults across countries. Each bar represents the average annual change in incidence rates over the past decade. (A) Countries where rates are increasing in adults aged 20–49 but declining or stable in those aged 50 and older. (B) Countries where rates are rising in both age groups, typically more sharply among younger adults. Source: Siegel et al. (2019), Gut.

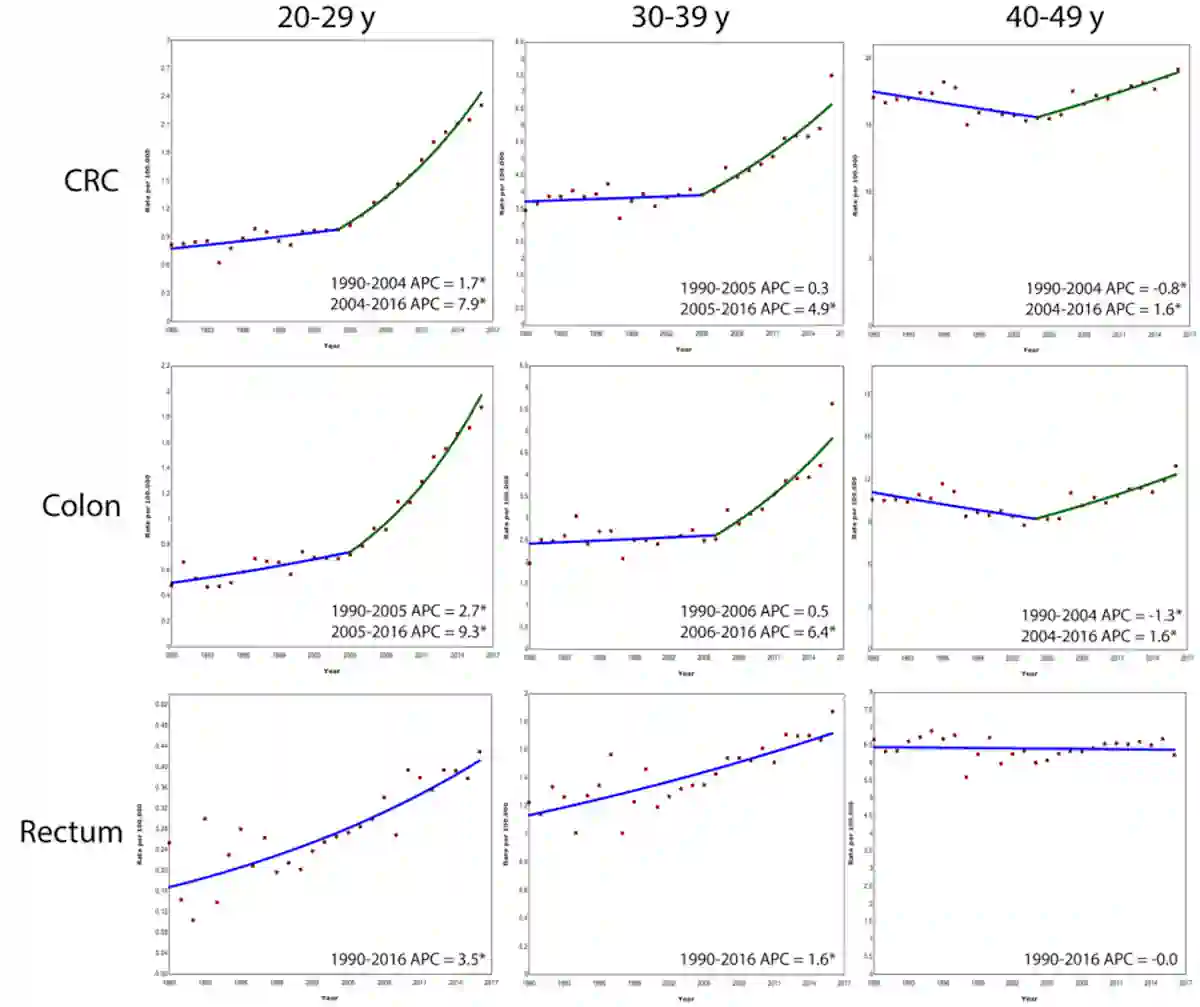

Moreover, the steepest rise in early-onset colorectal cancer is occurring in the youngest adults. A 2019 analysis of registry data across 20 European countries from 1990 to 2016 found that the incidence of colorectal cancer increased by 7.9% per year among those aged 20–29, compared with 4.9% and 1.6% in those aged 30–39 and 40–49, respectively. The trend is driven mainly by colon cancer, while rectal cancer rose more modestly (Figure 2). As people in their twenties are rarely screened, such sharp increases cannot be explained by overdiagnosis. Instead, the staggered rise across age groups points to a cohort effect, suggesting that each successive generations are being exposed to new or intensified risk factors.

But what could be the new risk factors?

Figure 2. Colorectal cancer is rising fastest in Europe’s youngest adults. Between 1990 and 2016, the incidence of colorectal cancer, particularly colon cancer, increased most sharply among 20–29-year-olds (nearly 8% per year since 2004), followed by 30–39-year-olds (about 5%) and 40–49-year-olds (about 1.6%). Source: Vuik et al. (2019), Gut.

Risk May Begin in Early Life

Adult risk factors such as obesity, alcohol, smoking and low physical activity undoubtedly play a role in colorectal cancer, but they cannot fully account for why rates in younger adults have surged only in recent decades. If these exposures alone were responsible, we would expect the rise in early-onset cases to have appeared alongside the well-documented increase in late-onset colorectal cancer in the 1950s, when many Western countries underwent dramatic lifestyle changes. Specifically, diets shifted toward greater consumption of processed meats, fast foods, edible oils, refined grains, high-fructose corn syrup and sugar, accompanied by reduced physical activity and increased use of antibiotics.

Instead, the pattern looks delayed: the first generations heavily exposed to “Westernised” conditions during childhood in the 1950s–1980s became young adults in the 1980s–2010s, precisely when the early-onset incidence began to climb. Therefore, scientists argue that the timing points to early-life exposures that drive the modern rise in early-onset colorectal cancer. Indeed, early life is a vulnerable window, marked by rapid cell growth, hormonal shifts and microbiome development, all of which can leave lasting biological imprints.

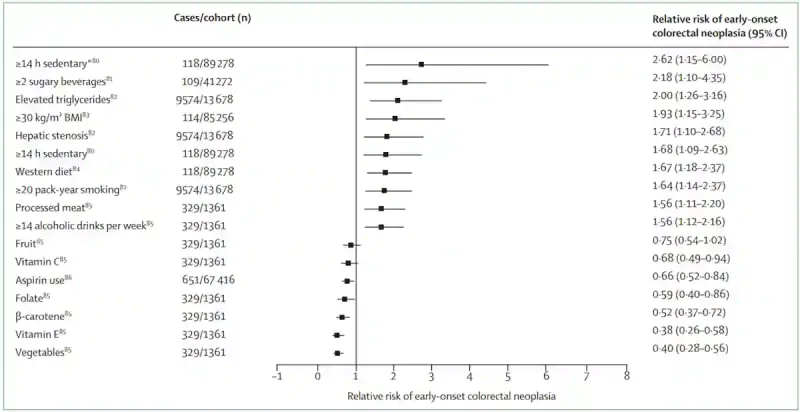

In other words, what happens during childhood or adolescent periods may set the stage for cancer decades later. If this is the case, the risk we often attribute to adult behaviours, such as diet, obesity or inactivity, may actually be the long-term consequence of exposures that began in childhood or adolescence (Figure 3). Supporting this, a few cohort studies have found that being obese in adolescence raises the risk of early-onset colorectal cancer, while being undernourished in childhood seems to lower it. Dietary patterns also matter: childhood and adolescent diets high in processed foods may elevate colorectal cancer risk.

Now, the question is: what exactly are these early influences doing at the molecular level that might accelerate colorectal cancer decades later?

Figure 3. Lifestyle factors linked to the risk of early-onset colorectal cancer. Sedentary lifestyle, sugary beverages, obesity, fatty liver, high triglycerides, smoking, heavy alcohol intake or eating processed or Western-style foods are all associated with a higher risk (relative risk >1). In contrast, consuming more vegetables and vitamins lowers the risk (relative risk <1). Source: Patel et al. (2022), The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

New Research Points to Child’s Gut Bacteria

A new clue comes from an extensive genomic study led by Marcos Díaz-Gay, Ph.D., of the University of California San Diego and Spanish National Cancer Research Centre, with more than 60 international collaborators. The study was recently published in Nature, the world’s leading scientific journal. This is one of the most ambitious attempts yet to decode why colorectal cancer is rising in younger adults, carried out by a global consortium of scientists.

Díaz-Gay et al. sequenced nearly 1,000 colorectal cancer samples from 11 geographically diverse countries to investigate how mutational processes vary across populations with different baseline cancer rates. Rather than focusing only on countries with the steepest rise in colorectal cancer in young adults, the researchers drew on cohorts spanning intermediate- and high-incidence settings where high-quality tumour samples were available. This strategy, part of the Mutographs Cancer Grand Challenge project, allowed them to identify mutational fingerprints that may explain why colorectal cancer is emerging earlier.

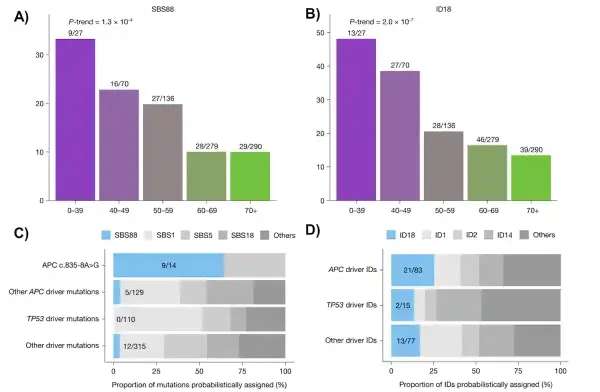

What they uncovered was both novel and pivotal. Unique mutational scars left by colibactin (i.e., a DNA-damaging toxin produced by certain E. coli strains) were far more common in colorectal cancers diagnosed before age 40 than in those diagnosed later in life. These colibactin fingerprints, catalogued as single base substitution 88 (SBS88) and insertion–deletion 18 (ID18), were roughly three times more frequent in early-onset colorectal cancers (Figure 4A, B). In total, about one in five colorectal cancers in the study carried signs of past colibactin exposure, and these patients were diagnosed at a younger age than those whose tumours lacked these colibactin signatures.

In fact, Díaz-Gay et al. showed that colibactin often damaged the APC gene, the gatekeeper that normally prevents cells from becoming cancerous. In about one quarter of colibactin-positive tumours, the first APC driver mutation can be directly attributed to this bacterial toxin. When looking at individual mutations, colibactin accounted for a disproportionately large share of APC mutational events (Figure 4C and D). As APC loss is usually the first step in catalysing colorectal carcinogenesis, an early hit by colibactin could jump-start the cancer process years ahead of schedule.

Intriguingly, many tumours with these colibactin-specific mutational signatures no longer contained the colibactin-producing E. coli strains by the time patients were diagnosed. This suggests that the mutations were likely inflicted much earlier in life, when the gut microbiome is still developing, and persisted long after the gut microbes themselves had vanished. In other words, colibactin-producing E. coli that colonise a child’s gut may leave permanent genetic scars that only reveal themselves as cancer decades later.

Figure 4. Bacterial DNA damage by colibactin is more common in early-onset colorectal cancer and strikes key cancer genes. (A, B) Distinctive DNA scars left by colibactin (SBS88 and ID18) are far more frequent in colorectal cancers diagnosed before age 40, and decline steadily with increasing age. (C, D) These bacterial scars can directly cause mutations in critical genes like APC, which normally prevents tumour growth. In some cases, colibactin was responsible for a large fraction of early APC driver mutations, helping explain how childhood exposure to these gut bacteria could set cancer in motion decades before diagnosis. Source: adapted from Díaz-Gay et al. (2025), Nature.

Prevention May Begin in Childhood

The new evidence from Díaz-Gay et al. reframes how we think about the rise in early-onset colorectal cancer. While lifestyle changes are still important, their study discovered a deeper layer: microbiome-driven DNA damage in early life may silently program risk across generations. If so, preventing or reducing exposure to colibactin-producing bacteria during childhood could curb the growing burden of this disease.

One of the main drivers of the growth of colibactin-producing bacteria like E. coli is arguably diet. In two large U.S. cohort studies tracking over 130,000 adults for more than three decades, a Western diet (rich in processed meat, sugar and refined grains) was linked to a 3.5-fold higher risk of developing colorectal cancer with abundant colibactin-producing E. coli. In animal experiments, a Western diet directly increases the growth of pathogenic E. coli in the gut microbiota. Therefore, ultra-processed dietary patterns may nurture the very microbes capable of seeding carcinogenic mutations in the colon decades before diagnosis.

Looking ahead, preventing early-onset colorectal cancer may require protecting the gut microbiota much earlier, beginning in childhood or adolescence. Reducing ultra-processed food intake, encouraging diets rich in fibre and plant-based foods, and limiting unnecessary antibiotic use are all practical steps that may discourage the growth of colibactin-producing bacteria. By shaping healthier gut microbiota early in life, we may be able to break the generational cycle and blunt the rise of colorectal cancer in the young.