The cancer was in remission, but the fatigue never let her recover. Beatrice M., once a high school art teacher and avid hiker, was diagnosed with breast cancer at age 54. She underwent surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and years of hormonal therapy to keep the disease at bay. But five years later, she still wakes up drained and comes home too exhausted to function. “I feel flat and worn out all the time,” she says. Despite normal blood results and no signs of depression, her fatigue rates a 6 to 8 out of 10 every day. For Beatrice and countless other cancer survivors, the cancer may be gone, but the exhaustion never leaves.

The Life-Altering Impact of Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF)

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is not just ordinary tiredness. According to the U.S. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), it is defined as “a distressing, persistent, and subjective sense of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment.” This level of fatigue occurs even without any significant mental or physical exertion, which often persists despite sufficient rest. Despite how common it is, CRF remains underreported, underdiagnosed and undertreated, leaving many patients and survivors silently struggling.

Since the late 1980s, incidences of CRF have been documented in clinical settings, typically after receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy. A multicentre study across 38 U.S. institutions found about 45% of cancer patients on active treatment reported moderate to severe fatigue. Even among survivors who have completed treatment and are cancer-free, about 30% still continued to experience significant fatigue. Similarly, in a longitudinal study of breast cancer survivors, 35% still reported feeling fatigued even 5 to 10 years later, especially among those who had a history of both chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

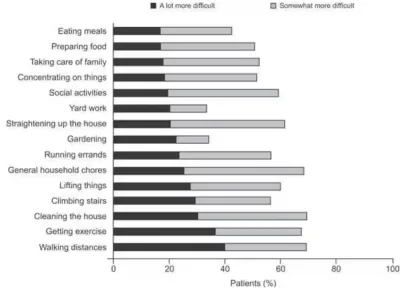

More concerningly, CRF is often rated by cancer patients as the most severe and disabling symptom they face during and after treatment compared to other symptoms like pain, nausea or depression. As many as 91% of cancer patients reported that fatigue interfered with their ability to live a normal life. Everyday tasks like preparing meals, doing housework or engaging in social interaction became overwhelming (Figure 1). CRF also affects productivity: over 75% of patients had to adjust their work conditions or leave employment altogether. Nearly 1 in 5 required help with basic household chores, creating additional financial costs from hiring assistance. These burdens may also spill over to families and caregivers, who may need to reduce their own working hours to care for loved ones affected by fatigue.

Figure 1. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on usual activities in patients with cancer who were treated with chemotherapy. Activities like walking, exercising, cleaning or socialising became somewhat or a lot harder for many. The darker bars represent tasks that became a lot more difficult, while the lighter bars indicate those that became somewhat more difficult. Source: Crawford and Gabrilove (2000) in Hofman et al. (2007), The Oncologist.

Beyond physical health, CRF also affects emotional and cognitive well-being. In one large survey, 90% of patients reported a loss of emotional control, and over 70% felt isolated or dejected. As follows, studies have linked CRF to higher rates of depression, anxiety and mood disturbance. A 2025 analysis presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting found that survivors experiencing CRF were 86% more likely to reduce recreational activities like walking or gardening. Depression further compounded this effect, leading to reduced participation in various lifestyle activities. Notably, these effects were more pronounced in women, who were more likely to report both CRF and depression.

These findings emphasise that CRF is a genuine and persistent condition, one that continues to affect patients and survivors long after their cancer has been treated. Yet, despite its prevalence and impact, the underlying mechanisms of CRF remain poorly understood. Why does this exhaustion linger, even when the cancer is gone and blood tests are normal? To address this question, we need to examine what might be driving CRF from within.

The Underlying Biology of Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF)

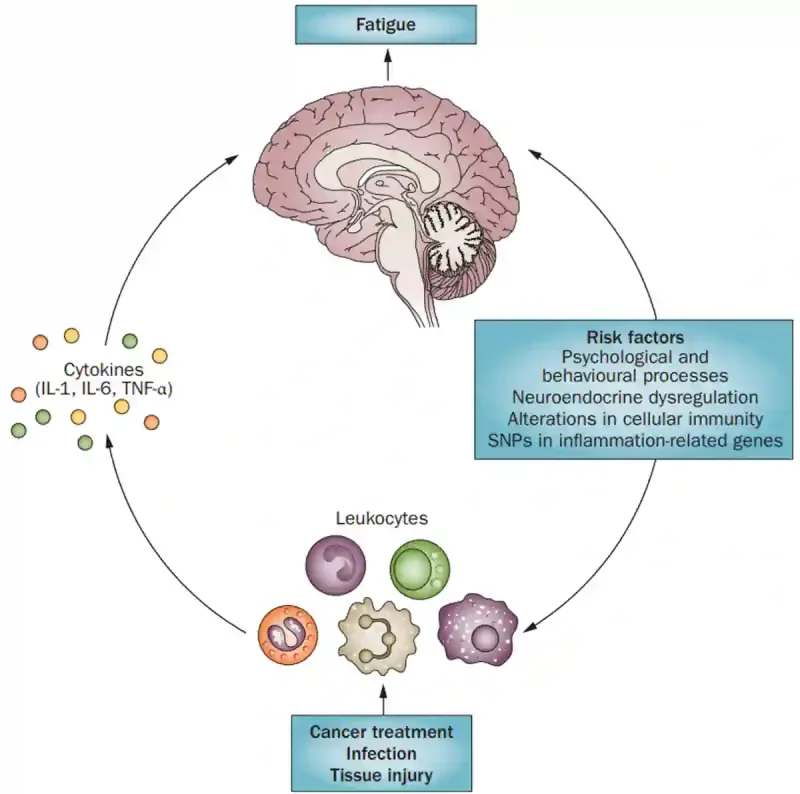

CRF is not simply a result of poor sleep or low fitness. While issues like medical conditions, medications or mood disturbances can contribute to fatigue, many patients with CRF remain otherwise healthy, suggesting that deeper physiological mechanisms are at play (Figure 2).

Among the most studied and consistently supported biological explanations is inflammation. Both tumours and therapies like chemotherapy or radiotherapy can trigger the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor- α (TNF-α). These cytokines can reach the brain via the vagus nerve or leaky areas of the blood-brain barrier. Once in the brain, they disrupt the synthesis and balance of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine and glutamate. This disruption contributes to symptoms of fatigue, brain fog and low motivation, collectively known as ‘sickness behaviour.’ Notably, inflammation-related fatigue can be long-lasting. Even years after treatment ends, survivors with CRF still show elevated inflammatory markers compared to non-fatigued peers.

Emerging research suggests that CRF may also be linked to deeper immune system changes. Studies have shown that some fatigued cancer survivors display altered gene expression in immune cells, particularly in genes involved in inflammation. In some cases, CRF has been associated with the reactivation of dormant viruses like cytomegalovirus (CMV). A study has found that nearly all patients undergoing chemotherapy experienced CMV reactivation, which coincided with flu-like symptoms and spikes in inflammatory signals. Hence, altered immune gene activity, along with the reactivation of latent viruses, may jointly sustain a pro-inflammatory state that fuels lingering fatigue during and after treatment.

Other biological systems may also be affected by CRF. For example, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been observed in survivors with CRF. The HPA axis is the body’s central stress response system, which links the brain and adrenal glands to control how we react to stress and regulate things like energy, mood and inflammation. Some studies have reported abnormal cortisol rhythms and reduced glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity in survivors with CRF, which may impair the body’s ability to shut off inflammation. (Glucocorticoid receptor binds to cortisol to regulate the HPA axis.) Moreover, CRF may involve an imbalance of the autonomic nervous system, with survivors showing heightened sympathetic (“fight or flight”) and reduced parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) activity, indicating a state of ongoing physiological stress. Akin to the HPA axis, the autonomic nervous system helps regulate immune activity, which may also influence CRF concurrently.

Together, these findings suggest that CRF is not just “in the mind.” It is tied to real biological changes, such as low-grade inflammation and imbalances across body systems (Figure 2). While not everyone experiences these effects the same way, they help explain why some people still feel exhausted even when cancer is in remission and other lab results appear normal.

Figure 2. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue (CRF). When the body undergoes cancer or tissue damage from chemotherapy or radiotherapy, immune cells release inflammatory signals called cytokines. These signals can travel to the brain and trigger fatigue, brain fog and low mood. This cycle may be worsened by stress, hormonal imbalances, immune system changes or even genetic factors that influence inflammation. Together, these factors can keep the fatigue going long after the cancer is gone. Source: Bower (2015), Nature Reviews in Clinical Oncology.

Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF): What Can We Do About It?

Unfortunately, there is no universal solution to CRF. Because its causes are complex and vary from person to person, researchers have explored a wide range of treatment approaches, including exercise, psychological support, medications and complementary therapies, with varying degrees of success.

Physical activity remains one of the most effective and well-studied interventions. One meta-analysis of 56 studies has found that regular exercise can reduce fatigue in both patients undergoing treatment and survivors. Even modest, tailored exercise plans can help, provided they are adjusted to a person’s energy levels and capabilities. However, most studies did not focus specifically on people already experiencing moderate to severe fatigue, so more research is needed to ensure exercise is feasible and safe for those who feel most depleted.

Psychosocial interventions like cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), education programs and support groups can also offer relief, especially when CRF is tied to unhelpful beliefs or emotional distress. CBT teaches patients how to challenge negative thoughts, conserve energy, and regulate sleep and activity patterns, which has shown lasting improvements in fatigue. In addition, early studies suggest that mind-body approaches, including meditation, yoga and acupuncture, may be helpful in managing CRF to some extent. These therapies may work by calming the nervous system and even reducing underlying inflammation.

Moving on, several pharmacological drugs have shown promise in addressing CRF. For example, hematopoietic growth factors like erythropoietin and darbepoetin may help when fatigue is caused by chemotherapy-induced anaemia. However, since most patients or survivors with CRF are not anaemic, these agents are unlikely to benefit the majority. Psychostimulants (e.g., methylphenidate) or anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., dexamethasone) have shown mixed results. They may be helpful for some patients, especially those with severe fatigue or ongoing inflammation, but are not recommended for routine use in all survivors with CRF.

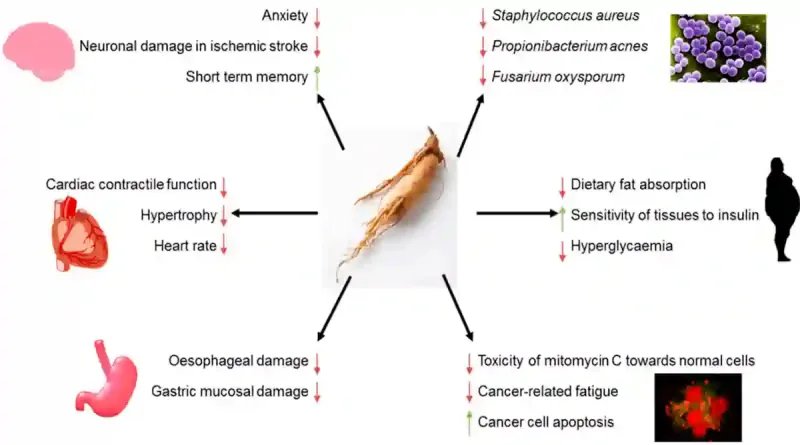

Complementary therapies using phytotherapy (therapeutic plant compounds) have also shown promising results in treating CRF. Among these, ginseng is the most studied, particularly Asian ginseng (Panax ginseng) and American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius). A recent meta-analysis of 12 clinical studies noted that both oral ginseng and ginseng injections are efficacious at reducing the physical symptoms of CRF, with injections showing greater efficacy in relieving cognitive fatigue. The U.S. National Cancer Institute even listed ginseng supplements as one of the management strategies of CRF. Some research has also supported the potential use of quercetin, stigmasterol and luteolin in managing CRF, although the evidence is still limited compared to ginseng. After all, ginseng’s popularity stems in part from its traditional role as an adaptogen, which improves the body’s resistance to stress and various diseases (Figure 3).

Ultimately, no single approach works for everyone. CRF can be driven by many factors, such as chronic inflammation, immune system changes, stress hormones, problems with the autonomic nervous system, or even how someone handles stress emotionally. The best treatment is often the one tailored to the individual’s specific biological and psychological profile. Just as cancer care is becoming increasingly personalised, so too should fatigue management.

Figure 3. An overview of ginseng’s health properties. Ginseng has been associated with improved cognitive function, reduced anxiety, enhanced insulin sensitivity, antimicrobial activity, and protection against cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and neurological damage. Ginseng may also reduce the toxicity of certain chemotherapeutic agents, promote cancer cell apoptosis, and help alleviate cancer-related fatigue (CRF), highlighting its potential as a complementary therapy in oncology. Source: Szczuka et al. (2019), Nutrients.

Conclusion

CRF is one of the most common yet least addressed burdens in oncology. Despite its profound impact on quality of life – interfering with daily function, emotional well-being and even treatment adherence – it is still under-recognised and undertreated. As more people survive cancer, care needs to go beyond just removing the disease. Helping patients heal from cancer must include helping them reclaim their energy, vitality and sense of normalcy too.