In this newsletter, we explore the relationship between menopause and cancer therapies, along with strategies to manage menopausal symptoms, whether they occur naturally or are triggered by cancer therapies. This is the first instalment of a three-part series on menopause symptom management, so stay tuned for the upcoming editions! Before diving into the specifics of therapy-induced menopause, let us first cover the fundamentals of menopause.

Menopause: Past to Present

Menopause: Symptoms and Triggers

For centuries, menopause was a misunderstood and feared aspect of a woman’s life. Regarded as a troubling affliction rather than a natural transition, women experiencing menopause were often subjected to harsh treatment. This perception persisted well into the Victorian era (1837-1901), where the medical establishment upheld the theory of ‘climacteric insanity’, claiming that the cessation of menstruation could trigger dangerous behaviour. As a result, many women were confined to asylums or subjected to invasive procedures, such as the surgical removal of ovaries, in a misguided attempt to cure their supposed mental instability.

By the late 19th century, medical and political reforms began to challenge these outdated views. Physicians started to recognise the hormonal shifts underlying menopause. This shift in perspective gradually paved the way for more humane treatments and a better understanding of menopause as a natural biological process marking the end of reproductive years.

Despite the progress, the current societal attitudes toward menopause still need improvement. Many women continue to face stigma, where they often feel compelled to hide their symptoms or refrain from seeking support, particularly in professional environments. Even today, no country has implemented legal protections for menopausal women in the workplace, highlighting a gap between medical understanding and societal support.

Menopause typically occurs between the ages of 45 and 55 when menstrual cycles stop permanently, marking the end of fertility. This transition happens due to the natural decline in reproductive hormones, such as oestrogen and progesterone. As these hormones play important roles in human physiology, such hormonal decline can affect bodily functions.

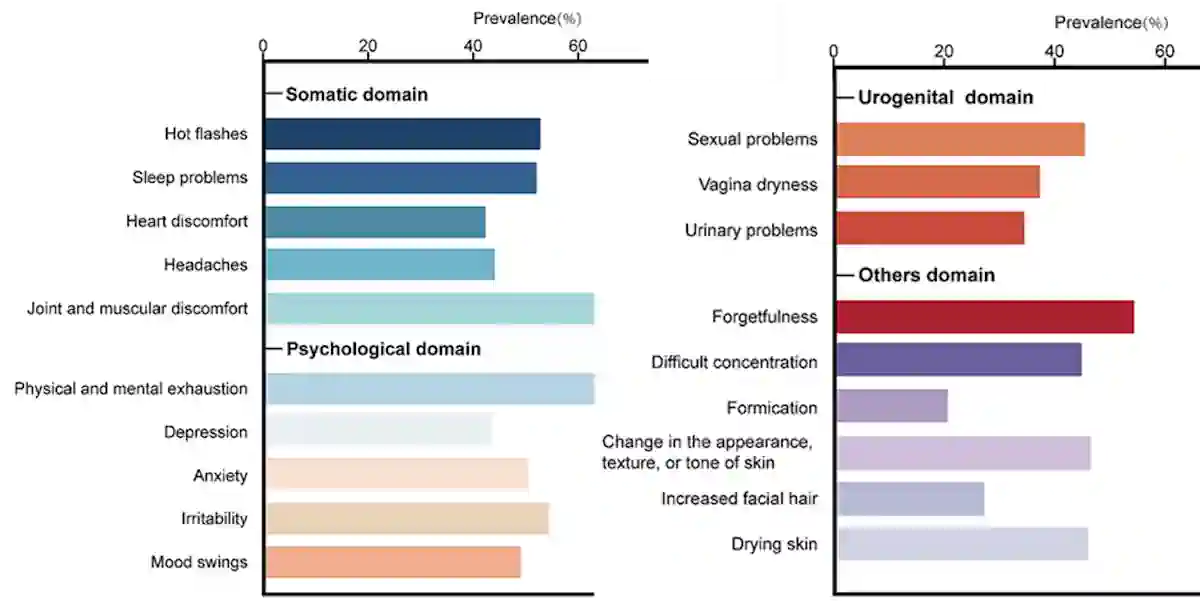

According to a 2024 meta-analysis, common menopausal symptoms include hot flushes, fatigue, mood swings, sleep problems, brain fog, joint pain and sexual problems. Other less frequent symptoms include chest discomfort, urinary problems, formication (i.e., sensation of insects crawling under the skin) and increased facial hair (Figure 1). These symptoms can impair a woman’s quality of life, affecting her physical, emotional and social well-being, although their severity varies from person to person. For most women, menopausal symptoms last an average of seven years, but some may experience them for up to 14 years.

Figure 1. The prevalence of each menopausal symptom, based on a meta-analysis of over 300 studies. Source: Adapted from Fang et al. (2024), BMC Public Health.

However, menopause is not always the result of natural ageing and can happen earlier than expected. Around 10% of women experience early menopause before 45 years old. One of the most common triggers of early menopause is cancer therapies, particularly chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with ovary-damaging effects. Surgical removal of the ovaries, often necessary to treat cancer or other medical conditions, also induces early menopause by eliminating the body’s ability to produce reproductive hormones. Other factors like genetics, chronic diseases and poor lifestyle habits (e.g., smoking) can contribute to early menopause. Concerningly, early menopause has been linked to long-term negative health outcomes, such as increased risks of osteoporosis, heart diseases and even early mortality.

Therapy-induced Menopause

Meta-analyses have estimated the global average age of natural menopause to be 49 years; however, pre-menopausal cancer survivors experience therapy-induced menopause earlier at 44 years. Despite the well-known impact of certain cancer therapies on fertility, this risk is often under-communicated to patients. About one-third of pre-menopausal cancer patients express dissatisfaction with the information provided by their physicians regarding the reproductive side effects of their treatment, including the risk of therapy-induced menopause.

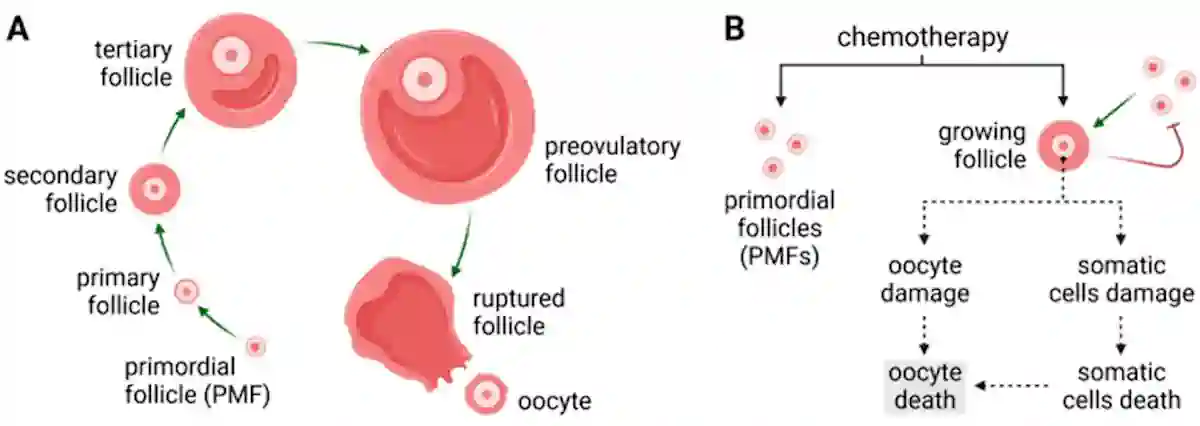

Chemotherapy drugs, particularly alkylating agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide and carboplatin), are known to cause ovarian damage. These agents work by adding alkyl groups to the DNA, causing DNA breakage in rapidly dividing cells. Unfortunately, this mechanism not only targets cancer cells but also damages healthy ovarian cells. Since women are born with a finite number of oocytes (immature egg cells), this damage accelerates ovarian ageing and the onset of therapy-induced menopause (Figure 2). Similarly, radiotherapy directed at the pelvic region can induce early menopause by damaging the ovaries or disrupting their blood supply.

Figure 2. (A) The process of ovarian follicle maturation. (B) Chemotherapy has toxic effects on the limited reserve of ovarian follicles, thus accelerating the onset of menopause. Source: Markowska et al. (2024), Cancers.

More concerningly, the risk of therapy-induced menopause is cumulative. Pre-menopausal women receiving either radiotherapy or alkylating agents alone face a 3.7-fold and 9.2-fold increased risk, respectively, compared to non-cancer patients. When both therapies are combined, the risk of therapy-induced menopause skyrockets to a 27-fold increase. Some women even experience menopause as early as their 30s, a condition known as premature ovarian insufficiency, after cancer therapies. In one cohort study of pre-menopausal women treated with both chemo- and radiotherapy, over 90% of them experienced therapy-induced menopause. The likelihood of menstrual cycles returning after therapy-induced menopause is slim, with fewer than 5% of women regaining ovarian function.

Hormone therapies, although not directly toxic to ovaries, may induce temporary menopausal symptoms. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs, e.g., tamoxifen) and aromatase inhibitors (e.g., anastrozole, letrozole) are designed to reduce oestrogen activity to inhibit the growth of hormone-sensitive cancers. Specifically, SERMs block oestrogen receptors in breast tissue, while aromatase inhibitors lower oestrogen levels by preventing the conversion of androgens into oestrogen. While these therapies do not destroy ovarian cells, they often mimic menopausal symptoms by suppressing oestrogenic activities.

As a 2024 paper in The Lancet, a highly prestigious medical journal, explains, “In pre-menopausal women, treatment for common cancers such as breast, gynaecological, haematological, and some low colorectal cancers will often cause ovarian damage, potentially inducing permanent menopause…This treatment can lead to more severe [symptoms] compared with natural menopause, particularly in younger women.”

Current Strategies to Manage Menopause

Managing menopausal symptoms, whether natural or therapy-induced, is critical to improving a woman’s quality of life. Treatment options include hormonal replacement therapy (HRT), lifestyle interventions, non-hormonal pharmacological therapies and non-pharmacological therapies. These treatments are particularly crucial for women experiencing therapy-induced menopause, as their symptoms are usually more severe compared to natural menopause.

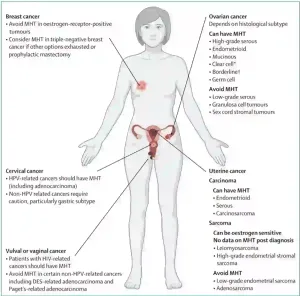

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved HRT, consisting of oestrogen with or without progestin (synthetic form of progesterone), as the first line of treatment for menopause. Clinical trials have demonstrated that HRT improves bone mineral density and lowers the risk of fracture in post-menopausal women. However, its impact on cardiovascular diseases remains controversial. A landmark systematic review reported that while HRT may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease, it also increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (blood clots) and stroke; thus, concluding that HRT cannot be broadly recommended for cardiovascular disease prevention. Moreover, HRT is contraindicated in women with hormone-sensitive cancers (e.g., breast, ovarian and uterine cancers), thrombotic disorders, and chronic liver disease. Such risks and contraindications make HRT unsuitable for many women, particularly those with therapy-induced menopause, who are frequently cancer patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Contraindications and use of hormonal replacement therapy (HRT), also known as menopausal hormonal therapy (MHT), in female-specific cancers. Source: Hickey et al. (2024), The Lancet.

Regarding lifestyle changes, the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology Guideline Group (ESHRE) emphasises the importance of adopting healthy habits to mitigate menopause-associated health risks, notably cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis. To support heart health, ESHRE strongly recommends smoking cessation, while weight-bearing exercises and calcium-rich diets are advised to maintain bone density to prevent fractures.

Non-hormonal pharmacological therapies involve using neurotransmitter-modulating drugs (e.g., antidepressants and neurokinin-3 receptor antagonists) to alleviate temperature-related symptoms in menopause, such as hot flushes and night sweats. These symptoms result from a dysregulated thermoregulatory centre in the brain, caused by reduced oestrogen signalling. By targeting neurotransmitters involved in this thermoregulation process, these drugs can help restore balance and mitigate temperature-related symptoms of menopause.

Non-pharmacological approaches include behavioural interventions and complementary therapies. Cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness training have been shown in clinical trials to reduce the severity of hot flushes, sleep disturbances and mood swings in menopausal women. Plant-derived compounds have also gained popularity as a complementary therapy to manage menopausal symptoms. For example, phytoestrogens are oestrogen-like compounds from plants, which can mimic the effects of oestrogen and offer symptomatic relief. Clinical trials have supported the effects of soy phytoestrogens in mitigating the severity and frequency of hot flushes in women undergoing natural or therapy-induced menopause.

The Need for Better Care

Despite existing treatment recommendations, a 2021 survey of cancer survivors with therapy-induced menopause revealed that only 32% were offered treatment by their physicians. Of those who received care, only 49% described it as ‘somewhat effective,’ and 34% deemed it entirely ineffective. Most of these women (60%) also expressed a need for additional support.

This vulnerable group, already grappling with the physical and emotional toll of cancer and the loss of childbearing capacity, often faces compounded difficulties due to the sudden onset of menopause. Menopausal symptoms can be disruptive to daily activities and pose long-term health risks, yet many women in this position are left without sufficient guidance. This highlights the urgent need for tailored, multidisciplinary treatment approaches to support their unique health needs.

In the next newsletter, we will explore the promising therapeutic potential of plant-derived compounds and how they can serve as complementary therapies to address the unmet medical need of managing natural or therapy-induced menopause.