For decades, the microbial world’s connection to cancer has focused on bacteria and viruses, such as Helicobacter pylori in stomach cancer and human papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical cancer. But what if we have been overlooking another key player? It turns out that fungi are also intertwined with cancer biology, influencing cancer progression in ways we are only beginning to understand. In this article, we delve into the unexpected role of the fungal microbiome, i.e., mycobiome, in cancer development. With fungal fingerprints now appearing in tumours across the body, an intriguing question arises: could antifungal therapies be used against cancer?

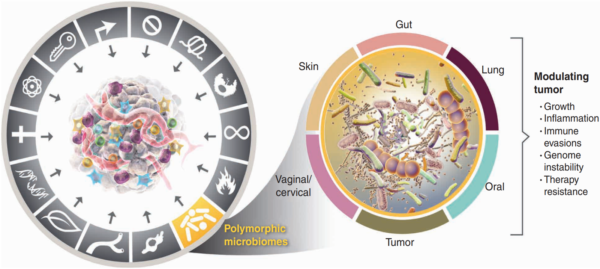

Carcinogenesis does not happen overnight. It is a gradual process where healthy cells undergo genetic changes that turn them into aggressive, fast-growing cancer cells. Back in 2000, world-renowned professors Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg introduced the idea that cancer follows a set of rules, which they called the “Hallmarks of Cancer.” Initially, they identified six traits cancer cells acquire to survive, grow and spread. As research advanced, however, so did our understanding of cancer. By 2022, this list had expanded to fourteen hallmarks, with the microbiome now recognised as a key player in carcinogenesis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.Polymorphic microbiomes are now recognised as one of the 14 hallmarks of cancer. Polymorphic means variable, referring to the microbiome composition that can change in response to different factors. These changes can impact carcinogenesis by influencing tumour growth, inflammation, immune evasion, genomic instability and therapy resistance. Source: Hanahan (2022), Cancer Discovery.

The microbiome refers to the body’s vast community of microbes, which are found primarily in the gut but also on the skin, mouth, vagina and lungs. While bacteria make up 90–99% of the microbiome, the remaining comprises viruses, archaea and fungi. The fungal component is called the mycobiome, first coined by Gillevet et al. in 2009. In healthy individuals, the gut mycobiome is dominated by yeast species from the Saccharomyces, Malassezia and Candida genera. However, dysbiosis (an imbalanced composition) can lead to overgrowth of certain fungal species, which has been linked to multiple diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, Alzheimer’s disease, liver diseases and cancer.

In 2017, scientists from Tongji University School of Medicine, China, conducted the first-ever analysis of the gut mycobiome in cancer patients, namely colorectal cancer (CRC). They were motivated by the growing recognition of mycobiome in diseases. As expected, CRC patients exhibited signs of fungal dysbiosis, marked by the overgrowth of Trichosporon and Malassezia species compared to healthy controls. These fungi are known to trigger pro-inflammatory responses, which can compromise gut barrier integrity (causing ‘leaky gut’) and fuel carcinogenesis. After all, chronic inflammation itself is one of the hallmarks of cancer.

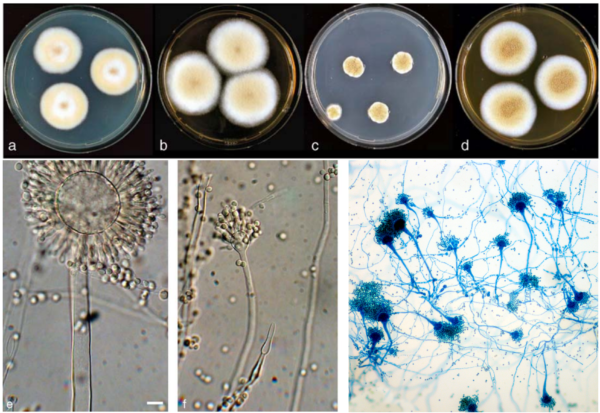

Further research into the gut mycobiome of CRC patients has also identified the prominent overgrowth of Aspergillus rambellii (Figure 2), a carcinogenic fungus. For example, a 2022 study synthesised seven previously published gut microbiome datasets with newly collected datasets to pinpoint six fungal species that are enriched in CRC patients, of which A. rambellii is the most abundant. Laboratory experiments then showed that A. rambellii induced carcinogenesis in both colorectal cells (in vitro) and mice (in vivo), providing cause-and-effect evidence for the involvement of this fungus in CRC development.

Apparently, Aspergillus rambelli produces aflatoxins, which are classified as Group 1 carcinogens, placing them in the same category as tobacco, alcohol, and ionising radiation. In fact, long-term exposure to such aflatoxins is already a well-established risk factor for liver cancer. A meta-analysis of 17 cohort studies estimated that the population attributable risk of fungal aflatoxins in liver cancer is 17%, meaning that aflatoxin exposure accounts for about one in six liver cancer cases worldwide. It is, therefore, unsurprising that A. rambellii residing in the gut is now identified as a carcinogen in CRC.

Figure 2. Morphology of Aspergillus species across different visualisation techniques. The top panel shows Aspergillus colonies growing on agar plates, while the bottom panel displays their microscopic structure under light microscopy and dye staining. Sources: Frisvad et al. (2005), Systematic and Applied Microbiology and Wikipedia Commons.

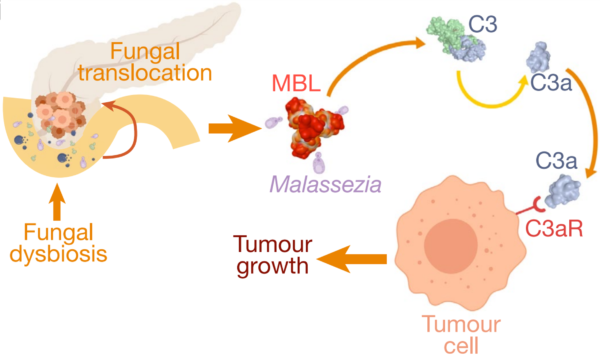

More evidence soon emerged that the gut mycobiome influences cancer in distant organs as well. A pioneering 2019 study at the New York University School of Medicine found that fungi from the gut can migrate to the pancreas, where they drive tumour growth. Pancreatic tumours contained 3,000 times more fungi than normal tissues, with Malassezia being the most abundant species in both mice and human patients. Removing fungi from the pancreas slowed tumour growth, while reintroducing Malassezia—but not other fungal species like Saccharomyces or Candida—accelerated it. Further experiments showed that Malassezia could activate mannose-binding lectin (MBL), which stimulates the C3 complement proteins to create a pro-inflammatory, immune-suppressive environment conducive to cancer growth (Figure 2). This discovery of a fungal microbiome within pancreatic tumours provided the first evidence of intratumoural mycobiome (intra– meaning ‘within’).

Further research has expanded on the concept of intratumoural microbiome. A 2022 study, for example, performed a pan-cancer analysis of 17,401 patient samples across 35 cancer types from four different populations. Their findings confirm that fungi exist in many human tumours at low levels. However, despite their low abundance, they are associated with important clinical outcomes:

- Breast cancer: The presence of intratumoural Malassezia species was linked to worse survival outcomes, decreasing overall survival probability from 90% to below 50% at 10 years of follow-up.

- Ovarian cancer: Patients with intratumoural Phaeosphaeria species had a shorter progression-free survival (i.e., from 498 to 135 days), which refers to the time lived without cancer worsening.

- Skin cancer: The presence of intratumoural Cladosporium species was associated with a 5-fold higher likelihood of not responding to immunotherapy, indicating a potential role of this fungal species in mediating immune evasion.

Figure 3. The role of fungal translocation from the gut to the pancreas in driving carcinogenesis. Specifically, the migration of Malassezia species can activate the mannose-binding lectin (MBL) pathway, leading to C3 complement activation that promotes tumour growth. Source: Aykut et al. (2019), Nature.

Fungi can infiltrate tumours through several mechanisms to shape the intratumoural mycobiome. One primary route is the disruption of the gut mucosal lining, which allows fungi from the gut to leak and invade tumour tissues. As the blood vessels of tumours are often disorganised and leaky, it may facilitate fungal entry from the bloodstream. Research on gastrointestinal cancers found that fungal DNA in tumours closely matches that in the blood, suggesting that fungi may travel via circulation before colonising new sites. Finally, the tumour microenvironment itself creates favourable conditions for fungal colonisation, such as low oxygen levels (hypoxia), excessive blood vessel growth (angiogenesis) and immune suppression, enabling the mycobiome within to thrive and persist.

A fungal community also exist as part of the oral microbiome. Research suggests that the oral mycobiome also plays a role in cancer development, particularly in nearby regions such as the oral cavity and certain head and neck cancers. However, compared to the gut and intratumoural mycobiome, the carcinogenic potential of the oral mycobiome is relatively less explored.

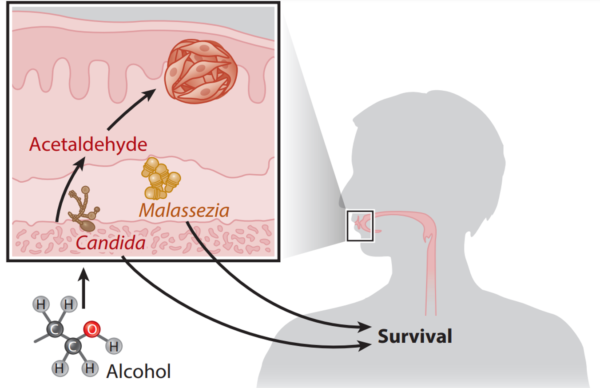

When scientists compared the oral mycobiome of patients with and without oral cancer, they found Candida albicans was overrepresented in cancer patients and linked to worse clinical outcomes. This finding aligns with another study showing that the abundance of oral C. albicans correlates with increased pro-inflammatory molecules in the saliva of head and neck cancer patients, reinforcing the pro-inflammatory role of C. albicans in carcinogenesis. In contrast, a greater abundance of Malassezia species was identified as a predictor of better overall survival among oral cancer patients (Figure 4). While the protective role of Malassezia remains unclear, possible explanations include competitive inhibition against other pathogenic fungi or immune modulation that enhances the body’s anticancer response.

Existing research on Candida albicans highlights several ways it may contribute to carcinogenesis. One factor is its ability to form biofilms, which are sticky microbial communities that resist the body’s immune responses. Additionally, C. albicans can produce nitrosamines, which are known fungal carcinogens like aflatoxins. Another concern is acetaldehyde, a toxic by-product of alcohol metabolism linked to oral cancer. C. albicans can also produce acetaldehyde as it metabolises alcohol, further amplifying cancer risk in people who consume alcohol. However, the impacts of the oral mycobiome in more distant cancers remain largely unexplored and warrant further investigations.

Figure 4. The oral mycobiome of oropharyngeal cancer patients. Candida species can metabolise alcohol to carcinogenic acetaldehyde, while Malassezia species are linked to better clinical outcomes. Source: Draganov et al. (2021), NPJ Breast Cancer.

As evidence piles on the role of fungi in cancer, the next pressing question is: can targeting the mycobiome be a viable strategy in cancer therapy? While research on antifungal interventions in oncology remains in its early stages, emerging findings suggest that modulating fungal communities could have profound implications for cancer therapy outcomes.

A breakthrough 2021 study from Cedars-Sinai Medical Centre, U.S., found that gut bacteria and fungi play opposite roles in shaping the immune system’s response towards radiotherapy. Using mouse models of breast and skin cancer, the study showed that depleting gut bacteria with antibiotics increased the proliferation of gut fungi like C. albicans and reduced the efficacy of radiotherapy. In contrast, depleting the gut fungi with antifungals led to improved radiotherapy outcomes. Hence, this preclinical study established a direct link that targeting the gut mycobiome with antifungals could improve cancer therapy results.

A 2023 study provided compelling evidence that targeting the intratumoural mycobiome with antifungals could inhibit pancreatic cancer. Researchers first discovered that pancreatic cancer cells produce interleukin-33 (IL-33) to attract pro-inflammatory immune cells to fuel tumour growth. Surprisingly, they found that fungi within the tumour were responsible for triggering IL-33 production. As follows, antifungal therapy managed to reduce the amount of tumour-promoting immune cells, resulting in smaller tumours and improved survival. Further analysis of human pancreatic cancer samples revealed high IL-33 in about 20% of patients, supporting the idea that disrupting the intratumoural-driven IL-33 with antifungals may help treat pancreatic cancer.

Interestingly, prior research has explored itraconazole, an oral antifungal drug, as a cancer therapy. A 1993 randomised clinical trial (RCT) tested if itraconazole could prevent fungal infections in immunocompromised patients and unexpectedly found that a subset of patients with blood cancer who received itraconazole had higher remission rates (cancer-free status) than those given a placebo. Following this, two RCTs in 2013 reported that itraconazole enhanced chemotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced lung and prostate cancers. While the investigators attributed these effects to itraconazole’s ability to block certain cell signalling pathways involved in cancer growth, its antifungal action likely played a role in improving cancer outcomes.

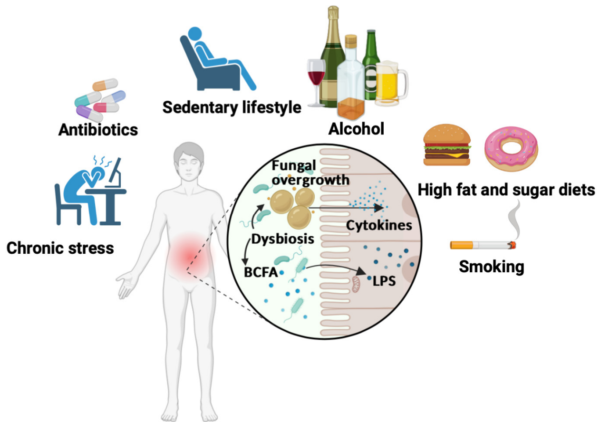

Moreover, diet and lifestyle influence the gut mycobiome. A high-sugar, low-fibre diet has been linked to the growth of Candida and Aspergillus species, which are known to promote carcinogenesis, as discussed above. Other factors that promote gut dysbiosis include chronic stress, antibiotic use, physical inactivity, alcohol and smoking (Figure 5), which are also cancer risk factors. Notably, various plant compounds – such as curcumin from turmeric, genistein from soy, resveratrol from grapes, bee pollen from flowers, quercetin from onions, baicalein from Baikal skullcap, and epigallocatechin gallate from green tea – have been found to inhibit the growth of clinically relevant fungi, including Candida and Aspergillus. While these plant compounds are already widely studied for their anticancer, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits, they may also target cancer through antifungal mechanisms.

As the mycobiome’s role in cancer gains recognition, future clinical research into antifungal interventions may open new avenues for cancer prevention and therapy. Targeting the mycobiome could one day be integrated into standard clinical practice to improve cancer care. Meanwhile, maintaining a balanced gut microbiome may be a simple yet powerful step in reducing the risk of pathogenic (disease-causing) and carcinogenic fungal overgrowth.

Figure 5. Unhealthy lifestyle factors in gut microbiome dysbiosis. Chronic stress, antibiotic use, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, poor diet and smoking can disturb gut microbiome balance, leading to overgrowth of harmful bacteria and fungi. This imbalance causes bacteria to release toxic lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and fungi to trigger inflammatory cytokines, fuelling chronic inflammation. Source: Jawhara (2023), Microorganisms.