How Patient’s Gut Microbiota Can Influence Cancer Risk and Progression

Introduction

Antonie Philips van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), aself-taught Dutch scientist, was fascinated with lens making and microscopy. Using his microscope, he discovered a world of “tiny animals” in his stool samples in 1681. Yes, van Leeuwenhoek was known as the Father of Microbiology, who discovered not only microbes but the gut microbiota as well.

However, it was not until the 21st Century that scientists realised the profound impact of the gut microbiota on disease development, including cancer. This concept was first illustrated by an altered gut microbiota composition with an increased abundance of the pathogenic Fusobacterium species in colon cancer patients compared to healthy individuals. Interestingly, transferring this species into mice triggered the development of colon cancer, as well as pro-inflammatory signature changes similar to colon cancer patients.

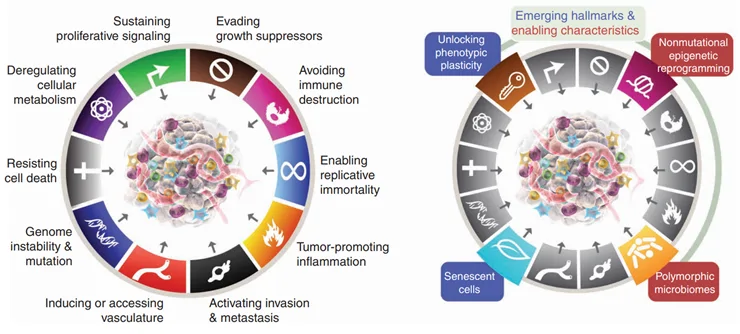

Now, the gut microbiota has been identified as one of the hallmarks of cancer by the American Association for Cancer Research in 2022 (Figure 1).

Understanding the intricate interplay between the gut microbiota and cancer is crucial, as it opens promising avenues for gut microbiota interventions in cancer treatment and prevention. However, given the immense diversity of cancer, this newsletter will only emphasise on breast and prostate cancers.

Figure 1. Left: The hallmarks of cancer model proposed in 2000 and 2011. Right: Four additional hallmarks of cancer were added to the 2022 model, including polymorphic microbiomes, which means highly variable microbiota in health and disease.

Gut microbiota in breast and prostate cancers

Breast and prostate cancers are among the most common cancers affecting women and men, respectively. Even with the leaps in medical technology, the rates of breast and prostate cancers remain on an upward trend. On the upside, however, recent research has uncovered the significance of gut microbiota in shaping the fate of these pervasive cancers, for the better or worse.

In a landmark 2021 study, scientists showed that a specific gut microbe called Bacteroides fragilis is capable of secreting B. fragilis toxin (BFT), which can translocate across the gut barrier into the bloodstream and end up in breast tissues in mice. Breast tissues exposed to BFT then exhibited abnormal cell activities related to inflammation, fibrosis, and growth, which are early indicators of cancer. Not surprisingly, the mice later developed full-fledged metastatic breast cancer.

In line with this, an increased abundance of Bacteroides species and decreased microbial diversity have been found in the gut microbiota of breast cancer patients compared to healthy women of similar age. Such altered gut microbiota further correlated with dysregulated oestrogen metabolism and inflammation control, which are conditions conducive to breast cancer.

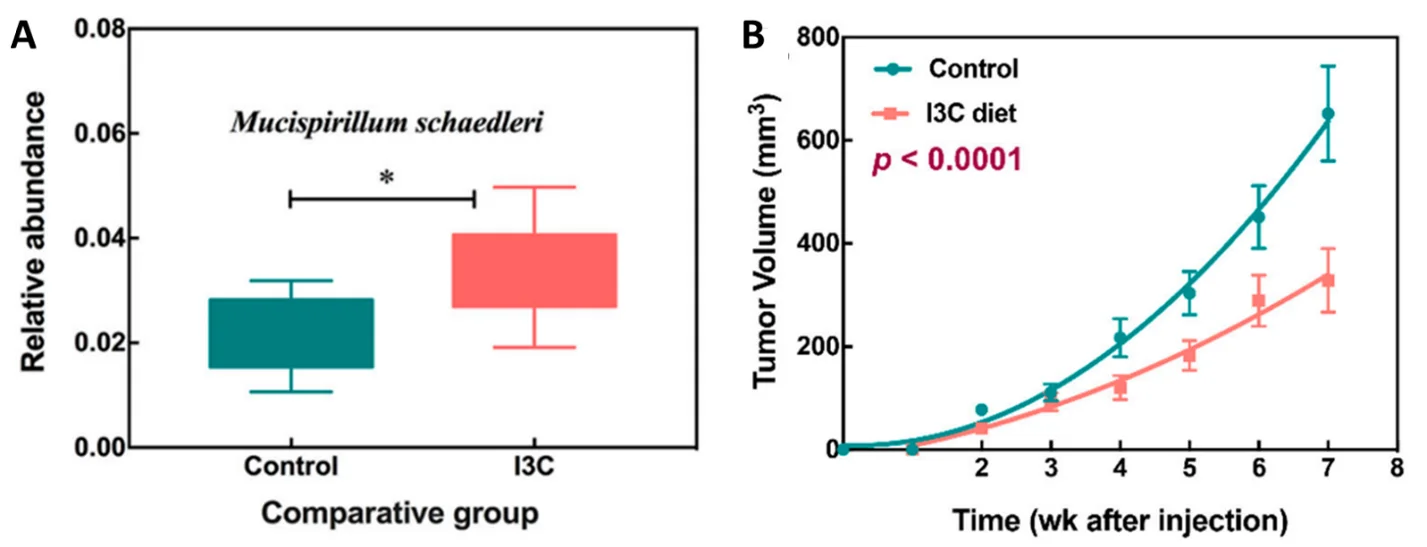

Compositional changes in gut microbiota have also been observed in prostate cancer patients. Notably, enriched harmful Bacteroides and Streptococcus species and diminished beneficial Faecalibacterium prausnitzii species were seen compared to non-cancer individuals. F. prausnitzii is a major producer of butyrate in the human gut, which is a known potent anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer compound. Studies have confirmed that prostate cancer cells underwent apoptotic cell death when exposed to butyrate, resulting in decreased tumour growth (Figure 2).

Encouragingly, studies have reported that interventions targeting the gut microbiota can mitigate the development and progression of cancer. Preclinical findings have shown that Lactobacillus probiotic species were beneficial in promoting anti-inflammatory activities, reducing breast tumour size, and even preventing breast cancer development if administered early. Similarly, one study demonstrated that Lactobacillus species stimulated natural killer cells and T-cells of the immune system to detect and attack prostate cancer cells.

Such findings align with human population studies, highlighting that regular consumption of Lactobacillus probiotics and prebiotics (e.g., fruits, grains and vegetables) cut the risk of breast cancer incidence by 35-50% and mortality by 10%. Prebiotics are fibres or plant compounds that nourish the gut microbiota. Studies have also consistently reported positive effects of plant-based diet or specific plant compounds (e.g., isoflavone from soybeans or indole-3-carbinol from cruciferous vegetables) in lowering prostate cancer risk by 30-40% in humans.

Figure 2. (A) Lower abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was observed in the gut microbiota of prostate cancer patients relative to healthy individuals (source: Golombus et al., 2017, Oncology). (B) F. prausnitzii is a major producer of butyrate (sodium butyrate and tributyrate), which shrunk tumour size in mice with prostate cancer by almost 50% (source: Kuefer et al., 2014, British Journal of Cancer).

The Pfeifer Protocol

Crafted by Ben Pfeifer, MD, Ph.D., and his team, the Pfeifer Protocol harnesses the potent anti-cancer attributes of selected plant compounds, honed over decades of clinical practice. While the anti-cancer mechanisms of such plant-derived compounds are diverse, they also influence the gut microbiota in ways that guard against cancer.

Take, for instance, BioBran – a key component included in the Pfeifer Protocol – which contains arabinoxylan extracted from rice bran. One study reported that mice fed with diet containing rice bran exhibited increased levels of Lactobacillus species in the gut microbiota, as well as improved dendritic cellular responses. As discussed earlier, Lactobacillus species are protective against the development and progression of breast and prostate cancers. Dendritic cells are equally important as they are responsible for alerting the immune system of cells that have turned cancerous.

Other components of the Pfeifer Protocol also augment the anti-cancer effects of gut microbiota. Here are a few examples involving extracts of indole-3-carbinol from cruciferous vegetables, curcumin from turmeric, and citrus pectin from fruit peel:

Overall, recent developments in cancer research have spotlighted the underappreciated involvement of the gut microbiota. However, present conventional cancer therapies do not foster a positive impact on the gut microbiota. Rather, such conventional therapies stress the body and have been linked to adverse changes in the gut microbiota. Fortunately, the Pfeifer Protocol’s holistic approach aligns with and leverages the cancer-modulating capacities of gut microbiota.

Figure 3. (A) Higher abundance of Mucispirillum schaedleri in the gut microbiota of mice treated with indole-3-carbinol (I3C) compared to no treatment. (B) Lower tumour growth in mice treated with I3C compared to no treatment. Source: Wu et al. (2019), Nutrients.