In the 1970s, Japanese scientist Satoshi Ōmura discovered Streptomyces avermitilis, a rare bacterium found in Japanese soil, and successfully cultured it in the laboratory. What makes this bacterium special is that, despite decades of global screening, it remains the only known natural source of ivermectin. Partnering with William C. Campbell at U.S.-based Merck & Co., they turned this microbial discovery into a breakthrough antiparasitic drug that would go on to eradicate river blindness and lymphatic filariasis, earning them the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. But ivermectin’s story may not end there. In recent years, scientists have uncovered its surprising potential as an anticancer agent. Could a decades-old discovery from a humble patch of soil now hold the key to a revolutionary cancer treatment?

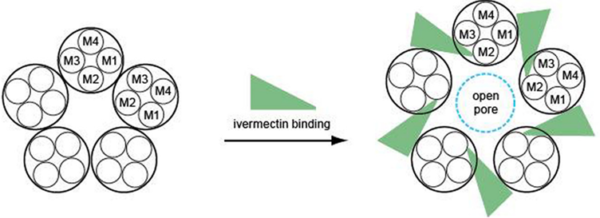

Before examining ivermectin’s direct anticancer effects, we need to understand how it works as an antiparasitic drug. Ivermectin binds to glutamate-gated chloride (GluCl) channels found in the nerve and muscle cells of parasites. By forcing these channels to remain open, ivermectin triggers an uncontrolled influx of chloride ions into the cells (Figure 1), thereby shutting down their ability to send signals. As a result, the parasite becomes paralysed and eventually dies. This mechanism is highly selective because humans and other mammals do not have GluCl channels, making ivermectin safe for therapeutic use.

Figure 1. How ivermectin opens glutamate-gated chloride (GluCl) channels. Ivermectin binds to the site between the M1 and M3 regions, causing them to shift apart and open a pore in the channel to allow entry of chloride ions. Source: Wolstenholme (2012), Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Ivermectin’s ability to manipulate chloride ion flow actually makes it a promising candidate for cancer therapy. In 2010, scientists from the Ontario Cancer Institute, Canada, discovered that ivermectin could act as an ionophore – a molecule that helps transport chloride ions across cell membranes – while studying its effects in leukaemia (blood cancer) cells. Compared to normal cells, cancer cells rely more heavily on chloride channels to regulate their electrical balance and cell volume for their survival and rapid growth. By increasing chloride influx, ivermectin disrupts this delicate balance, creating oxidative damage and pushing cancer cells toward apoptotic cell death. This ionophore mechanism makes ivermectin particularly promising as a targeted anticancer agent that spares healthy cells, which are more resistant to chloride imbalances.

Besides chloride ion manipulation, ivermectin also exhibits other forms of anticancer actions:

- Mitochondrial disruption: Cancer cells have high metabolic demands, requiring a constant supply of cellular energy (ATP) to fuel their rapid growth. Laboratory studies on cancer cells showed that ivermectin could inhibit mitochondrial complex I, an enzyme complex in the electron transport chain responsible for ATP production. This inhibition reduces ATP availability, thus depriving cancer cells of energy. Moreover, ATP depletion itself acts as a cellular stressor, triggering oxidative stress that damages DNA, lipids and proteins. This metabolic collapse ultimately accelerates apoptotic cell death of cancer cells while sparing healthy cells.

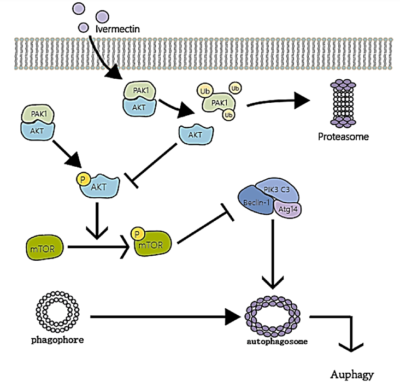

- Autophagy Induction: Cancer cells have a survival mechanism called autophagy, a process where they break down and recycle their own damaged components to stay alive under stress. However, too much autophagy can push cancer cells toward self-destruction. Research shows that ivermectin triggers excessive autophagy in cancer cells by blocking the PAK1/Akt pathway, a key regulator that prevents uncontrolled self-digestion (Figure 2). In this manner, ivermectin starves tumours from within by forcing cancer cells to consume themselves beyond repair.

- Targeting Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs): One of the greatest challenges in cancer care is CSCs, a small but powerful group of cancer cells that can self-renew, resist treatment and drive cancer recurrence. These CSCs are often responsible for tumour regrowth after chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Ivermectin, interestingly, has been found to disrupt the stemness of these aggressive CSCs by downregulating activities of stem-like genes (e.g., NANOG, SOX2 and OCT4). By dismantling CSCs, ivermectin helps improve therapy effectiveness and reduce the likelihood of cancer recurrence.

Figure 2. The autophagy induction mechanism of ivermectin in cancer cells. Ivermectin breaks down PAK1 to disable the Akt/mTOR pathway. This loss removes the brakes on autophagy, forcing cancer cells to self-digest. Source: Tang et al. (2011), Pharmacological Research.

Thus far, we have discussed how ivermectin directly destructs cancer cells through mechanisms such as chloride ion manipulation, mitochondrial impairment, autophagy induction and cancer stem cell (CSC) inhibition. However, ivermectin’s anticancer capacity extends beyond direct toxicity. Ivermectin also weakens cancer’s defences, making previously drug-resistant tumours vulnerable to chemotherapy and immune-evasive cancer cells more detectable by the immune system.

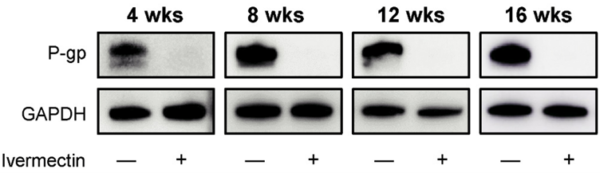

Chemotherapy often fails not due to ineffective drugs, but because tumours evolve ways to evade them. A major driver of this resistance is P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a molecular pump that expels chemotherapy drugs from cancer cells before they can exert their toxic effects. Over 90% of deaths in chemotherapy-treated patients are linked to drug resistance. Many cases of cancer recurrence arise from residual cancer cells that developed resistance to the initial chemotherapy used, allowing them to proliferate and drive tumour regrowth.

Interestingly, the first study exploring ivermectin’s anticancer potential, conducted in 1996, focused on its ability to target P-gp. Specifically, scientists at Strasbourg University, France, demonstrated that ivermectin restored drug retention via P-gp inhibition in multidrug-resistant human leukaemia cells. As a result, ivermectin-treated leukaemia cells became 60-fold more sensitive to common chemotherapy drugs, such as vinblastine and doxorubicin. More recent studies confirmed that the P-gp inhibitory effect of ivermectin extends beyond leukaemia, successfully reversing drug resistance in colorectal, lung and breast cancer cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Western blot analysis of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression in lung cancer cells treated with and without ivermectin. Ivermectin abolished P-gp expression within four weeks, as shown by the absence of western blot bands. Note: GAPDH serves as the loading control, ensuring equal protein levels in each condition (i.e., − or + ivermectin). Source: Hayashi et al. (2024), Anticancer Research.

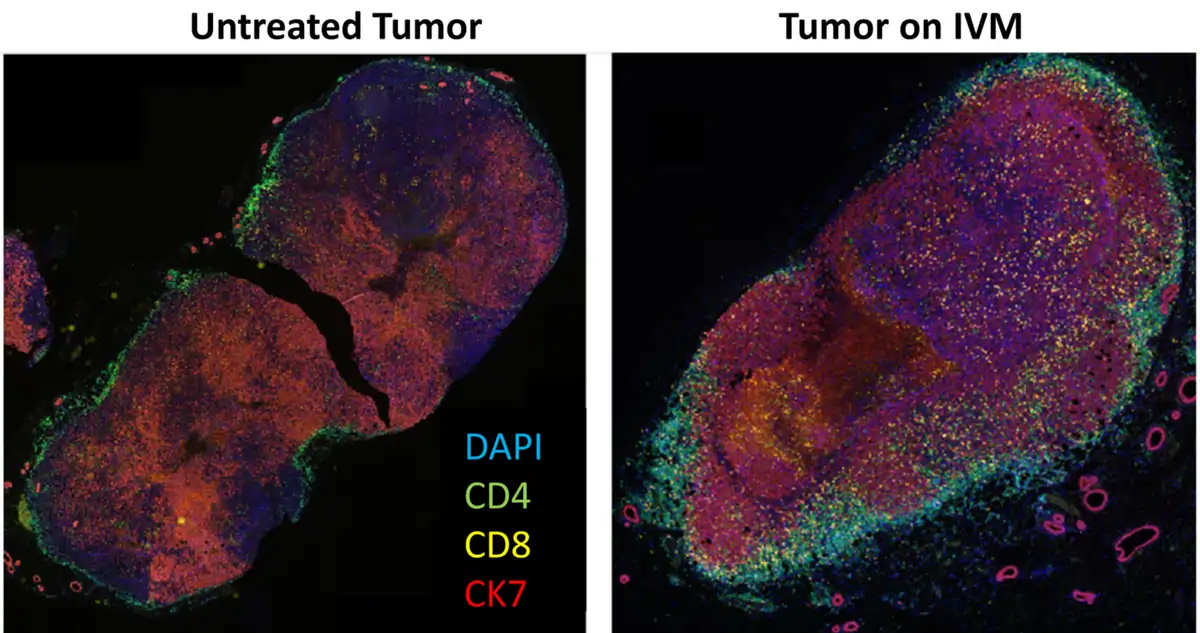

Cancer cells often evade immune detection by suppressing immune cell activity, particularly by preventing T-cells from infiltrating the tumour. T-cells are immune cells that destroy abnormal cells, including cells that turn cancerous. For this reason, multiple forms of immunotherapies rely on harnessing and empowering the natural anticancer effects of T-cells. Therefore, ‘cold’ tumours remain hidden from the immune system, allowing them to grow unchecked and making immunotherapies like checkpoint inhibitors ineffective.

However, recent research shows that ivermectin can turn cold tumours ‘hot,’ making them more visible to immune attack. In a 2021 study, scientists at the Beckman Research Institute, U.S., demonstrated that ivermectin induced immunogenic cell death in breast tumours, triggering the release of danger signals like ATP, calreticulin and HMGB1. These molecules act as immune alarms, which alert and recruit T-cells into the tumour, thus transforming an immune-silent environment into an immune-active one (Figure 4). The study further showed that ivermectin enhanced the efficacy of anti-PD1 therapy (an immune checkpoint inhibitor) in boosting T-cell infiltration and achieving complete tumour regression in a mouse model of immune-evasive breast cancer – results that anti-PD1 therapy alone failed to accomplish.

Figure 4. Staining of untreated and ivermectin (IVM)-treated breast tumours for T-cell infiltration. CD4 helper T-cells are stained green, CD8 cytotoxic T-cells are stained yellow, and cancer cells expressing the CK7 biomarker are stained red. The results revealed a notable increase in both CD4 and CD8 T-cell infiltration within the IVM-treated tumour. Source: Draganov et al. (2021), NPJ Breast Cancer.

While ivermectin directly kills cancer cells through the multifaceted mechanisms discussed above, it also plays an indirect role in dismantling tumour defences, tackling two of the greatest challenges in modern oncology: drug resistance and immune evasion. However, laboratory findings alone are not enough. Without rigorous clinical trials, ivermectin risks becoming yet another overlooked breakthrough. The real question is not whether this decades-old drug holds promise, but whether the scientific and medical communities are willing to look beyond conventional treatment paradigms and explore unconventional options, even if they come from the unlikeliest of sources – like ivermectin derived from a Japanese soil bacterium.

Thankfully, a search of the ClinicalTrials.gov database for ongoing clinical trials investigating ivermectin in cancer patients returned two registered studies, both from the U.S.:

- NCT05318469: A phase I/II clinical trial at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, is evaluating ivermectin in combination with balstilimab (an anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor) for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Patients will receive oral ivermectin with intravenous balstilimab on a 3-week cycle for up to 35 cycles. Researchers will assess whether this combination improves tumour shrinkage, progression-free survival and overall survival. If successful, this trial could offer a new immunotherapy strategy for TNBC, a type of aggressive cancer known for resisting conventional therapies.

- NCT02366884: A phase II clinical trial at Dr. Frank Arguello Cancer Clinic is examining an unconventional therapy approach called atavistic chemotherapy, based on the theory that cancer cells behave similarly to primitive single-celled organisms. This trial is testing whether FDA-approved antibacterial, antifungal and antiparasitic drugs (including ivermectin) can benefit patients with advanced or metastatic cancers. The primary goal is to assess tumour regression over six months. If successful, this trial could provide new insights into repurposing antimicrobial agents for oncology.

Ivermectin’s unexpected anticancer potential challenges the belief that only cutting-edge, expensive and newly designed drugs can transform cancer therapy. The abilities of ivermectin to attack cancer through multiple mechanisms highlight the untapped power of drug repurposing, a strategy that could make effective therapies more accessible and affordable. With ivermectin no longer under patent protection, it can be manufactured and distributed globally as a low-cost generic drug. Its decades-long safety record further positions ivermectin as a well-established option for repurposing. While clinical validation is still needed, the potential of ivermectin is a reminder that some of the most promising solutions in cancer care may already exist, waiting to be rediscovered.