If there is one antioxidant that has quietly fascinated scientists for decades, it is lycopene. Found abundantly in tomatoes and other red-coloured fruits, lycopene has been linked to cancer protection, but the evidence has often been conflicting and inconclusive. Now, a huge meta-analysis of over 120 studies, covering nearly 2.7 million people, offers a clearer view: High lycopene levels in your blood are associated with a meaningful reduction in cancer risk and mortality. Yet, as with many nutrition-cancer debates, the full story is far from straightforward. Let us unpack what this massive analysis tells us (and what it does not).

The Anticancer Background of Lycopene

New Insights on Lycopene’s Anticancer Capacity

In 1986, the landmark Health Professionals Follow-up Study enrolled nearly 48,000 men initially free from cancer, tracking their diets and health over the next six years. By 1995, the findings made headlines: out of 46 fruits and vegetables studied, four foods stood out for cutting prostate cancer risk by as much as 35%: tomatoes, tomato sauce, tomato juice and pizza (oddly), which together accounted for over 80% of the participants’ lycopene intake. In fact, lycopene emerged as the only carotenoid with a statistically significant association with the risk reduction of prostate cancer. This study was arguably the first evidence spotlighting tomato-based products and lycopene as potential anticancer agents in humans.

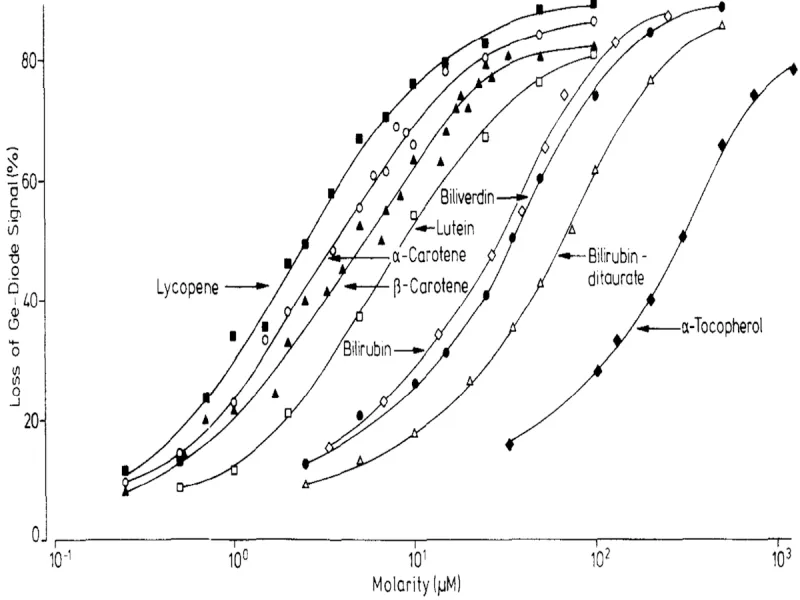

What makes lycopene so intriguing is its unique biological behaviour among antioxidants. Unlike the typical carotenoid, lycopene cannot be converted into vitamin A, but it is the most potent scavenger of singlet oxygen (Figure 1), a highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can damage DNA and promote cancer formation. Lycopene is also highly lipophilic, accumulating in fatty tissues like the liver, adrenal glands and the prostate. Furthermore, cooking and processing tomatoes, as in tomato sauce or pizza toppings, enhance the bioavailablity of lycopene, which raises blood levels more effectively than raw tomatoes.

Over the years, hundreds of studies have explored the potential anticancer effects of lycopene, but findings have remained inconsistent. Prior meta-analyses were often fragmented, focusing on single cancer types or combining studies with varying designs. Few accounted for how lycopene levels in the blood compare to dietary intake, and even fewer mapped the dose-response relationship to clarify whether more lycopene translates into greater protection. To this end, the new meta-analysis by Iranian scientists Balali et al., published in Frontiers in Nutrition, compiled data of nearly 2.7 million people from over 120 cohort studies to provide the most rigorous assessment of the role of lycopene in cancer prevention to date.

Figure 1. How different antioxidants reduce the signal of reactive oxygen. This graph compares how effectively natural antioxidants like lycopene, beta-carotene, lutein and vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) can neutralise singlet oxygen, measured by the loss of the Ge-diode signal. The steeper the curve, the better the antioxidant is at reducing the signal of singlet oxygen. Lycopene shows strong activity even at lower concentrations, outperforming several other antioxidants. Source: Di Mascio et al. (1989), Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

For context, a meta-analysis is a powerful research method that combines the results of multiple studies to draw a more reliable conclusion. It employs a systematic review process, which thoroughly searches the literature to capture all relevant studies, minimising the risk of cherry-picking studies conforming to one’s hypothesis. In the case of lycopene and cancer, this approach cuts through decades of scattered and sometimes conflicting research to derive a consensus on whether lycopene has protective effects against cancer.

In the latest meta-analysis, Balali et al. found that simply eating more tomatoes did not show any meaningful effects on cancer prevention. Even when they investigated individual cancer types, eating more tomatoes did not seem to make a difference in cancer risk. However, people who ate more tomatoes had an 11% lower risk of dying from cancer, a modest but statistically significant finding. Therefore, tomatoes alone may not prevent cancer from developing, but they might help improve survival outcomes if cancer occurs.

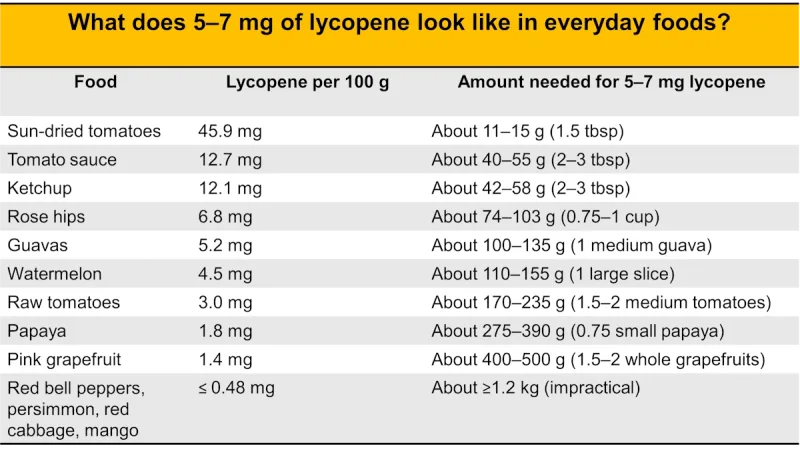

The findings became more compelling when Balali et al. shifted the focus to lycopene intake specifically. People who consumed the most lycopene in their diets had about 5% lower overall cancer risk and, notably, 16% lower risk of cancer death. The benefits were not uniform across all cancer types, though. Lycopene’s strongest protective effect was seen for lung cancer, with a remarkable 17% drop in the risk of developing it among high consumers. Balali et al. also mapped a dose-response relationship, where the optimal intake seems to be around 5–7 mg of lycopene per day, with little to no extra benefit going beyond 10 mg/day. So, what does that amount look like? We provided examples in Table 1.

Table 1. Common sources of lycopene, and how much is needed to reach the 5–7 mg daily target. Source: Integrative Cancer Care.

Perhaps the most revealing insights came from looking at lycopene levels in the blood, rather than just dietary intake. Blood measurements are crucial because they reflect how well your body absorbs lycopene. In the meta-analysis, people with higher blood levels of lycopene had 11% and 24% lower risks of cancer development and death, respectively. For lung cancer mortality, the reduction was even sharper at 35% in those with the highest blood lycopene levels. The benefits were also noticeable for breast and prostate cancer risk, where higher blood lycopene was linked to a 10–14% reduction in risk. Hence, the anticancer potential of lycopene may depend more on your body’s levels instead of just what is on your plate.

That said, even a meta-analysis of this scale has its limitations. Observational cohort studies cannot establish cause and effect by default, since other factors like overall diet quality, genetics or lifestyle habits could influence the observed results. Data is also limited for cancers less studied in lycopene research (including endometrial, head and neck, renal, liver and skin cancers), where too few studies exist to draw firm conclusions. Although blood lycopene levels appear to be the strongest predictor of reduced cancer risk and mortality, it remains unclear how much dietary lycopene is needed to reach protective levels. After all, the metabolism and absorption of dietary lycopene can vary widely between individuals. Still, the results do show a compelling signal: achieving and maintaining higher lycopene levels – most likely through a diet rich in red-coloured fruits or even supplementation – could be a simple, low-risk way to protect against cancer and support long-term health.

The Broader Health Benefits of Lycopene

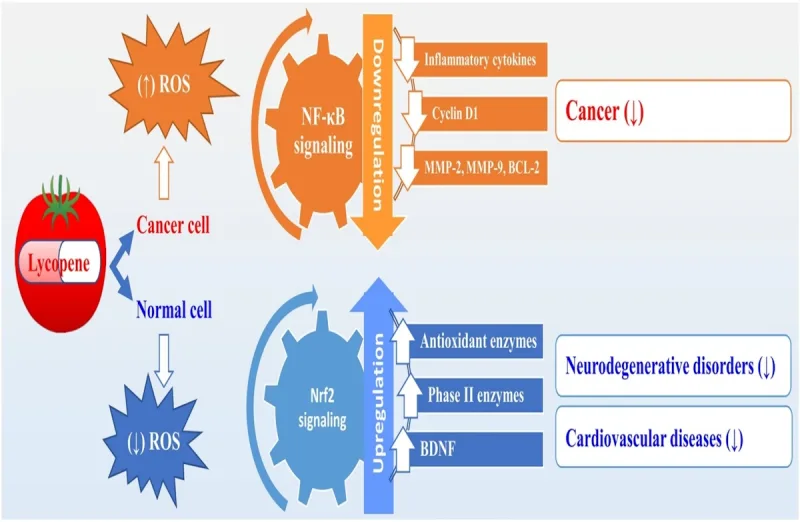

Further research suggests that the benefits of lycopene may extend beyond oncology. As a potent antioxidant agent, lycopene can influence biological processes that underlie age-related decline. For instance, a 2024 study found that higher blood levels of lycopene were linked to longer telomere length. As telomeres shorten over time, they are used as a standard marker of cellular ageing. Intriguingly, lycopene may act as a calorie restriction mimetic, reproducing some of the metabolic effects of reduced caloric intake, such as inhibiting ageing-related genes in the brain and heart tissues. The anti-inflammatory effects of lycopene are also widely documented, where it can suppress the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and activation of the NF-κB cellular pathway, known as the master regulator of inflammation.

Consequently, observational studies have documented the risk reduction of multiple chronic diseases in individuals with high lycopene intake. For example, a meta-analysis of 25 cohort studies reported that individuals with higher dietary intake or blood levels of lycopene had 15-25% lower risks of stroke and cardiovascular diseases, as well as up to 40% reduction in all-cause mortality. Indeed, clinical studies show that lycopene may help mitigate the damaging effects of oxidative stress on blood vessels and oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, thus promoting cardiovascular health (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lycopene’s antioxidant actions in cardiovascular health. Lycopene helps reduce oxidative stress by inhibiting the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and lipid peroxidation. It also activates key antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), which collectively enhance endothelial (blood vessel) function and support cardiovascular protection. Source: Przybylska and Tokarczyk (2022), International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

As a fat-soluble antioxidant, lycopene can cross the blood-brain barrier, allowing it to counteract the oxidative stress and inflammation in neurons in the brain. In animal models of Parkinson’s disease, for example, lycopene supplementation could reverse motor impairments and decrease neuronal cell death. Lycopene also improved memory performance, reduced oxidative stress and inflammation in the hippocampus, and restored levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. BDNF is a key molecule that supports neuroplasticity and cognitive function, which is often used as a biomarker of neuronal health. Although most of the current neuroprotective evidence of lycopene comes from preclinical studies, they nevertheless shed light on the potential role of lycopene in protecting brain health, which warrants further clinical investigations.

Overall, these diverse effects indicate that lycopene is not just an anticancer molecule, but a multi-functional carotenoid across biological systems. By reducing the risk of cancer and other chronic diseases, lycopene offers benefits beyond what you might expect from a single nutrient. While more research is always needed in nutritional science, the evidence so far is encouraging. Whether through lycopene-rich foods or supplementation, sustaining higher levels of lycopene may be one of the most accessible and safest investments for long-term health.