Imagine being diagnosed with cancer that may never affect your health – or undergoing aggressive treatment that offers little chance of improving your life expectancy. For many men with prostate cancer, this is the unsettling reality. While advances in medical technology have revolutionised detection and treatment, they come with a hidden cost: the overtreatment of cancers that may not require intervention. This article explores the hidden toll of prostate cancer overtreatment and strategies to overcome this pervasive problem.

Diagnosis and Grading of Prostate Cancer

Overtreatment of Prostate Cancer

Accurate diagnosis and grading of prostate cancer are essential for guiding effective treatment plans. However, advancements in diagnostic tools have also resulted in the overdiagnosis of indolent (slow-growing and unlikely harmful) tumours, contributing to the overtreatment of prostate cancer. Consequently, many patients undergo unnecessary interventions for cancers that may never progress. Before we discuss the issue of overtreatment, let us first understand the primary diagnostic and classification tools of prostate cancer today:

- Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Testing: Elevated levels of PSA, a protein produced by the prostate gland, in the blood can indicate the presence of cancer. However, non-cancerous conditions (e.g., prostatitis or benign prostatic hyperplasia) may also raise PSA levels.

- Digital Rectal Exam (DRE): The DRE involves a doctor inserting a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum to feel the prostate gland for abnormalities in size, shape or texture. While simple and cost-effective, the accuracy of DRE is variable, so it is usually used alongside PSA testing.

- Biopsy: A biopsy, the gold standard for cancer diagnosis, involves using a thin needle to extract tissue samples from the prostate, typically through the rectum or perineum. These samples are examined under a microscope to confirm cancer.

- Advanced Imaging Techniques: Multiparametric (multi-technique or multi-layered) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans are helpful in identifying suspicious areas for targeted biopsies and differentiating between low-risk and aggressive cancers.

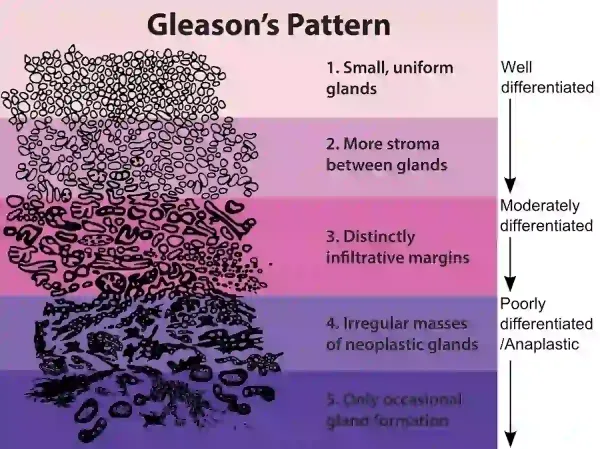

Once prostate cancer is confirmed through a biopsy, the next step is to grade the cancer’s aggressiveness to guide treatment decisions. The Gleason Score system categorises prostate cancer into Grade Groups 1 to 5 (GG1-5) based on the structural patterns of cancer cells observed under a microscope. Lower scores (GG1) indicate well-differentiated cells that are less likely to spread, while higher scores (GG5) reflect poorly differentiated, more aggressive cancer (Figure 1). Typically used with PSA testing and clinical staging, the Gleason Score helps classify patients into low-, intermediate- or high-risk categories.

Figure 1. Prostate tumour grading is categorised into Grade Groups (GG) 1-5 according to the Gleason scoring system. Source: Public Domain.

Grade Group 1 (GG1), corresponding to the lowest Gleason Score, has become a focal point in discussions about the overtreatment of prostate cancer. Emerging evidence suggests that GG1 often behaves more like a benign condition than a life-threatening cancer, with less than a 1% risk of cancer metastasis (spread) or mortality. Moreover, GG1 is highly prevalent in older men, suggesting that it could be part of the normal ageing process of the prostate gland.

Using data from the U.S. National Cancer Database, a 2024 study analysed over 36,000 men with low-risk prostate cancer (GG1, PSA <10 ng/ml) and reported that surgical rates dropped from 55% in 2010 to 40% in 2016. While this reflects the growing adherence to a more conservative management for low-risk cancers, 40% of men in the study were still overtreated with surgery. The likelihood of overtreatment was further linked to increased biopsy sampling, suggesting that greater diagnostic intensity may drive unnecessary interventions.

To address prostate cancer overtreatment, modern protocols have prioritised identifying higher-grade disease (GG2 and above) for treatment. However, even higher-grade prostate cancers are being overtreated, especially in men with limited life expectancy. A 2024 study analysing data from over 240,000 men with localised (early-stage) prostate cancer found a troubling trend: between 2010 and 2019, interventions for intermediate-risk cancers rose from 38% to 60% among men with <10 years of life expectancy. Similarly, interventions for high-risk cancers increased from 17% to 47% in men with a life expectancy of <5 years.

“We found this pattern surprising,” Timothy Daskivich, MD, a urologic oncologist at Cedars-Sinai, U.S., who conducted the study, said in a press release. “Prostate cancer patients with life expectancies of less than five or 10 years were being subjected to treatments that can take up to a decade to significantly improve their chances of surviving cancer, despite guidelines recommending against treatment.”

Therefore, while some progress has been made in reducing overtreatment of low-risk cancers, aggressive therapies are increasingly being applied to men who are unlikely to live long enough to benefit from them – because of:

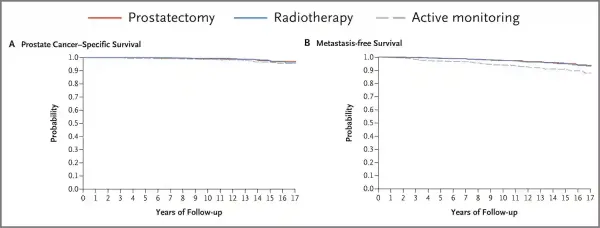

- Limited Time to Benefit: For men with a life expectancy under 10 years, localised prostate cancer is unlikely to advance to a life-threatening stage within their remaining lifespan, offering little to no benefit from aggressive treatment (Figure 2).

- Competing Health Risks: Many men with limited life expectancy have serious comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes. Managing these conditions may be more beneficial than treating the prostate cancer.

- Significant Side Effects: Conventional cancer therapies (e.g., surgery or radiotherapy) often cause various side effects, which may outweigh their potential benefits for men with limited life expectancy.

- Misalignment with Guidelines: Recent guidelines advise against aggressive treatment for men with limited life expectancy unless the cancer poses imminent harm.

Figure 2. Long-term survival outcomes for localised prostate cancer over 17 years. Limited treatment benefit was observed for prostatectomy (surgery) and radiotherapy within 5-10 years compared to active monitoring (no immediate treatment). Panel A shows the probability of death specifically from prostate cancer, while Panel B illustrates the probability of death due to cancer metastasis. Source: Hamdy et al. (2023), The New England Journal of Medicine.

Overtreatment of prostate cancer further imposes substantial financial and personal burdens. It is estimated that overtreatment costs an additional $18,000 per patient compared to active surveillance. On a national scale, avoiding unnecessary treatment for the approximately 80% of newly diagnosed men with low-grade prostate cancer – who are unlikely to die from the disease – would save the U.S. $1.32 billion annually. Meanwhile, experts have also highlighted potential financial incentives tied to specific treatments as a key factor perpetuating the persistence of overtreatment. Beyond the financial strain, overtreatment profoundly impacts patients’ quality of life, often resulting in preventable long-term complications such as urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction and bowel issues.

Strategies to Prevent Overtreatment

To minimise the overtreatment of prostate cancer, strategies must target the key factors driving unnecessary interventions: overdiagnosis, the psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis, and a lack of awareness about less invasive approaches to managing cancer.

The widespread use of PSA screening and biopsies has led to the overdiagnosis of indolent, non-life-threatening tumours. Hence, refining diagnostic practices is crucial to better identify patients at genuine risk of aggressive disease. Risk-adjusted screening – tailored to factors such as life expectancy, family history and baseline PSA levels – can help prioritise detection efforts for higher-risk individuals. Similarly, biopsies should be more selective, avoiding men with mildly elevated PSA levels and no other risk factors. Advances in imaging techniques and genomic tests also offer more precise differentiation between low-risk and high-risk cancers, reducing unnecessary interventions for clinically insignificant cases.

The psychological impact of a prostate cancer diagnosis often compels patients to seek aggressive treatments out of fear and the misconception that all cancers must be eradicated immediately. To counter this, clear and compassionate communication from healthcare providers is essential. Clinicians should emphasise that not all prostate cancers require urgent treatment, especially for low-risk and even certain intermediate-risk tumours. This approach can help alleviate anxiety and guide patients toward more informed decisions.

A lack of awareness about alternative approaches also contributes to overtreatment. In the last 15 years, clinical guidelines have increasingly endorsed the use of active surveillance for low-risk and even some intermediate-risk prostate cancers. Active surveillance monitors prostate cancer through regular PSA tests, imaging and biopsies, with treatment initiated only if the tumour shows signs of progression. This strategy rests on the principle that curative treatment remains possible within the “window of cure” if needed, allowing patients to postpone or even completely avoid cancer therapies and their side effects, thus reducing overtreatment.

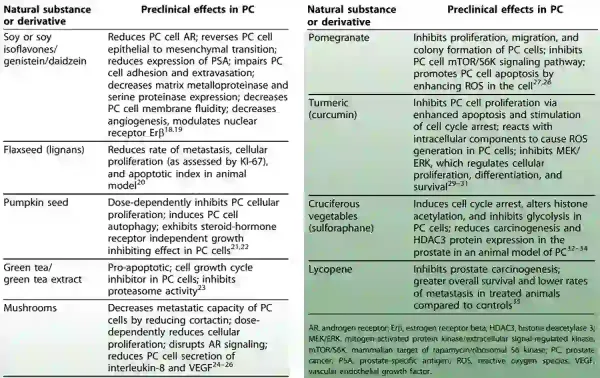

Moreover, there is a growing interest in integrative active surveillance (IAS), which builds upon standard active surveillance protocols by incorporating evidence-based interventions, such as dietary changes, exercise and tailored supplementation. The principles of IAS align with accumulating evidence that nutrition and lifestyle factors can influence prostate cancer progression. For example, plant polyphenols from sources like green tea, turmeric and soy have demonstrated powerful anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-cancer properties (Figure 3). Exercise has been shown to improve psychological well-being while reducing biomarkers of prostate cancer progression. Thus, IAS also supports broader metabolic health, offering added benefits since prostate cancer patients often face elevated risks of cardiovascular disease.

Figure 3. Documented effects of certain plant compounds against prostate cancer in preclinical models involving lab-cultured cells or animals. Source: Lucius (2023), Integrative and Complementary Therapies.

In essence, IAS not only reduces the fear of a “do-nothing” approach commonly associated with active surveillance but also empowers patients by giving them actionable steps to manage their health. At Integrative Cancer Care, we bring this philosophy to life through the Pfeifer Protocol, a comprehensive approach that integrates various therapeutic plant compounds to support our patients toward a healthier quality of life. We are committed to patient-centred cancer care, prioritising well-being above unnecessary interventions and ensuring that medical decisions are aligned with outcomes that truly matter to each individual.