Back in 2021, we raised a concern many still hesitate to talk about: the very procedure used to diagnose cancer, the needle biopsy, may inadvertently help it spread in rare cases. Our original report focused on prostate cancer, describing how puncturing the tumour with a biopsy needle can dislodge some cancer cells, allowing them to potentially seed a new tumour elsewhere. Today, an increasing number of studies confirm what we cautioned about then: tumour seeding or dissemination can occur following biopsy. The overall risk may be low but not negligible, and it has been observed across multiple cancer types. The question is no longer if it happens, but how we can better protect patients from this under-recognised risk.

Tumour Seeding or Dissemination: Overlooked Risks of Biopsy

Evidence for Tumour Seeding Following Biopsy

Most cancers today are diagnosed through needle biopsies. They allow clinicians to sample and examine the tumour directly to determine the presence and aggressiveness of cancer cells, which helps guide treatment decisions. However, not many are aware that this routine diagnostic step carries a small biological risk of dislodging some cancer cells from the tumour. Because of its perceived rarity – and the difficulty in quantifying its exact prevalence and long-term impact – many physicians do not discuss such risks with patients. Yet growing evidence in recent years suggests this risk deserves closer attention, especially among patients who may be unknowingly exposed to it.

Tumours are not structurally stable. Unlike healthy tissue, cancer cells often have weak cell-to-cell adhesion, making them easier to dislodge when physically disrupted. When pierced by a biopsy needle, some cancer cells can break free. These dislodged cells may travel along the needle track into nearby tissues or enter nearby blood vessels. From there, they may circulate in the bloodstream as circulating tumour cells (CTCs), which are capable of colonising and seeding new cancer growths in distant organs.

As oral pathologists Karnam et al. wrote (slightly paraphrased) in a widely cited 2014 paper, “Tumour cells are easier to dislodge due to lower cell-to-cell adhesion. Oftentimes, to obtain sufficient samples during a needle biopsy, the tumour is penetrated several times. This repeated puncturing may seed tumour cells into the needle track or spill them into the circulation. Several case studies have shown that, following diagnostic biopsy, some patients developed cancer at multiple sites and had CTCs in the bloodstream.”

This leads to two overlooked risks of needle biopsy:

1. Tumour cell seeding into nearby tissues punctured along the needle tract.

2. Tumour cell dissemination into the bloodstream via punctured blood vessels.

Let us begin with the first problem: biopsy-related tumour seeding. For many years, the evidence was limited to case reports describing the formation of new tumours along the needle path after biopsy. Pathologists Macklin et al. from the University of Oxford and its affiliated hospital once noted that the true incidence of biopsy-related tumour seeding is currently under-recognised in a 2019 commentary. In recent years, however, more studies have brought clearer evidence that such instances occur in about 1–10% of biopsied cases, depending on the cancer type. For breast cancer, the number seems to range from 3–5%:

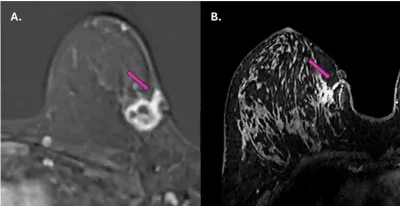

- A 2025 study used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess whether the cancer had spread along the path of a previous needle biopsy in a group of 62 patients with breast cancer. In three of them (4.8%), cancer cells were found growing in the biopsy tract, sometimes reaching the skin and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 1). These findings were confirmed by ultrasound and repeat biopsy.

- A 2023 study examined the surgical specimens of 4,405 breast cancer patients, finding the presence of tumour cells in scar tissues left behind by needle biopsies in 133 patients (3%). Fortunately, none experienced cancer recurrence, likely because most of them had hormone-sensitive tumours and received additional hormonal therapy, which effectively suppressed any remaining cancer cells.

For other cancer types, more data suggest that the incidence of biopsy-related tumour seeding may range from 1% to as high as 10%. For example, a 2025 report found that tumour seeding following liver cancer biopsies occurred in just 0.6% of cases. Similarly, in prostate cancer, the rate appears to be around 1–2%. For kidney cancer, the incidence rate of biopsy-seeded tumours may be 6%, based on a recent German study. In thyroid, bone and soft tissue cancers, the rate of tumour seeding post-biopsy has reached 10% in some studies. These figures confirm that biopsy-seeded tumours are a real risk, which can lead to life-threatening cancer recurrence or metastasis in rare instances.

Figure 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showing tumour spread along the needle biopsy path in two breast cancer patients (purple arrows). In both cases, the cancer appears to have extended from the original tumour site toward the skin and surrounding tissue along the path created by the biopsy needle. Source: Fleury et al. (2025), Cureus.

Evidence for Tumour Dissemination Following Biopsy

For the second risk of biopsy, the dissemination of tumour cells into the bloodstream, the evidence is clearer and easier to quantify. Unlike tumour seeding into surrounding tissues, which requires imaging or tissue sampling to confirm, blood tests can directly detect circulating tumour cells (CTCs). Studies as early as the late 1990s have detected a spike in CTCs shortly after a biopsy in about 15–30% of patients with prostate or breast cancer. These CTCs were not present before the biopsy and were absent in those whose biopsy results were negative (no cancer), indicating it was the biopsy that dislodged tumour cells into the bloodstream.

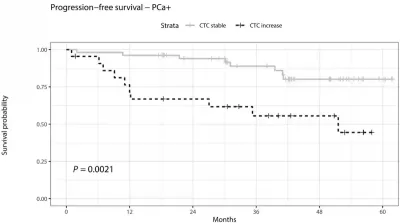

Subsequent studies have further shed light on the clinical consequences of these biopsy-disseminated CTCs. For instance, a 2020 study from the University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany reported that CTCs rose sharply within 30 minutes after biopsy in men diagnosed with prostate cancer. These CTCs also correlated with worse outcomes over the next five years: men with a biopsy-related spike in CTCs were 12-fold more likely to experience cancer progression or death compared to those whose CTC levels remained stable (Figure 2). “[This] should ring a bell for the community, as it provides important evidence that traumatic biopsies are not neutral on disease progression,” oncologists from the University of Basel and its affiliated hospital in Switzerland commented upon reading the German study. “Further, it cannot be ruled out that the injury caused by needle biopsy may have an effect on local progression toward an invasive stage, for instance, by perturbing the arrangement of tumour cells close to blood vessels or by promoting inflammation.”

Figure 2. Percentage of prostate cancer patients who remained free from cancer progression or death over time. Those with a rise in CTCs after biopsy (dashed black line) had worse survival outcomes compared to those with stable CTC levels (light grey line) over 60 months (5 years). The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.0021). Source: Joose et al. (2020), Clinical Chemistry.

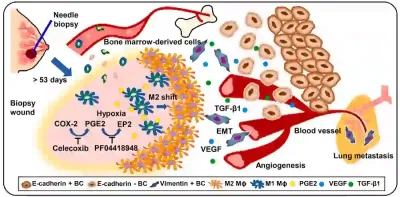

Such hypothetical concerns were later supported by a 2023 preclinical study from the U.S., which uncovered alarming biomechanistic evidence regarding the potential harm of biopsy. Beyond simply dislodging cancer cells into circulation, needle biopsies may biologically alter tumours in ways that promote their spread. In this study, researchers performed biopsies on mice implanted with human breast cancer cells. Tumours that were biopsied were significantly more likely to metastasise, particularly to the lungs, than those left untouched. In addition to dislodging tumour cells, the puncture damage from the biopsy also activated pro-metastatic changes in the tumour environment, such as increased blood vessel formation (angiogenesis), inflammation and cancer cell mobility. Together, these changes made it easier for cancer cells to travel to distant organs. Although this study was done with animals, it provides cause-and-effect evidence under controlled conditions, making it possible to elucidate a theoretical model of how biopsy could potentially trigger metastasis (Figure 3).

A previous clinical study has shown that breast cancer survivors who underwent a core needle biopsy faced higher risks of metastasis appearing 5–15 years later compared to those who had a fine-needle aspiration biopsy. While fine-needle aspiration is less invasive, it only collects cells or fluid, limiting diagnostic accuracy. In contrast, core needle biopsy retrieves a larger tissue sample, allowing more detailed examinations, but it also carries a risk of dislodging tumour cells. Importantly, the increased risk of late metastasis was not due to patients having more aggressive cancer at baseline. The study adjusted for tumour stage, grade and therapy received, leaving the biopsy received as the only plausible explanation.

Figure 3. A theoretical model of biopsy-induced metastasis (cancer spread) based on animal experiments. After a biopsy is performed, the wound left behind may trigger a chain reaction inside the tumour. It draws in immune cells from the bone marrow, increases inflammation and blood vessel growth (angiogenesis), and activates pro-cancer signals like transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). These changes can help tumour cells break away, enter the bloodstream, and eventually spread to other organs like the lungs. Source: Kameyama et al. (2023), Cell Reports Medicine.

The Biopsy Protection Protocol

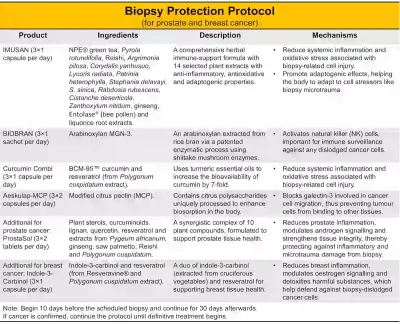

As we have seen, needle biopsies carry a small but real risk of dislodging tumour cells, either along the needle tract or into the bloodstream. Yet, abandoning biopsies is not the solution. Delaying or avoiding biopsy often results in late diagnoses and treatment, leading to poorer clinical outcomes. For instance, 3–6% of breast cancers are already metastatic (stage IV) at diagnosis, missing the critical window of early intervention. The question, then, is not whether we should use needle biopsies, but how we can better protect patients from potential risks. To this end, we have designed a biopsy protection protocol for patients with breast and prostate cancer who will be undergoing a biopsy (Figure 4):

- IMUSAN: 3×1 capsule per day

- BIOBRAN: 3×1 sachet per day

- Curcumin Combi: 3×1 capsule per day

- Aeskulap-MCP: 3×2 capsules per day

- ProstaSol: 3×2 tablets per day (additional for prostate cancer)

- Indole-3-Carbinol: 3×1 capsule per day (additional for breast cancer)

*Note: Start 10 days before the scheduled biopsy and continue for 30 days afterwards. If the biopsy confirms cancer, the protocol should be maintained until definitive treatment (e.g., surgery, radiation or chemotherapy) begins.

How does this biopsy protection work? What is the rationale behind it? Each product in the protocol is selected to target a specific point in the metastatic cascade triggered by biopsy-related tumour cell seeding or dissemination (Figure 4). Here is how it works:

Tissue damage response: As biopsy punctures the tissue, it creates microtrauma that triggers inflammation and oxidative stress. While these responses occur to facilitate wound healing, they also promote cancer growth and metastasis if left unchecked. The protocol then introduces IMUSAN, a 14-herb formula with anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and adaptogenic properties, to help the body recover from and adapt to biopsy-induced stress and inflammation. Moreover, Curcumin Combi delivers curcumin at seven times the typical bioavailability and resveratrol to further dampen inflammation, neutralise free radicals and inhibit tumour-promoting pathways. In recent months, we have also been using a new delivery method of curcumin: a patented lozenge, Curcumin Sublingual. This melt-in-the-mouth tablet dissolves rapidly in the mouth, allowing for the absorption of curcumin through the oral mucosa, bypassing the digestive tract. This method has been shown to achieve curcumin blood levels comparable to intravenous (into the vein) infusion. In fact, a human study showed that a small, mouth-dissolving lozenge produced twice the curcumin blood levels compared to a much higher capsule dose. This fast-acting delivery method may offer additional benefits for post-biopsy recovery and could be considered in future versions of the protocol.

Anticancer immunity: Biopsy also risks dislodging cancer cells into nearby tissues or the bloodstream. To enhance the immune system’s ability to eliminate these stray cancer cells, the protocol implements BIOBRAN containing arabinoxylan extract from rice bran. Studies show that arabinoxylan is a potent activator of natural killer (NK) cells, a key component of the immune surveillance against cancer cells.

Cancer cell migration: To prevent dislodged cancer cells from colonising other tissues, the protocol includes Aeskulap Modified Citrus Pectin (MCP), which contains citrus-derived polysaccharides uniquely processed to enhance biosorption. MCP is rich in galactose that binds to galectin-3, a protein involved in cancer cell migration. By keeping galectin-3 occupied, MCP prevents stray tumour cells from latching onto other tissues.

Direct anticancer effects: Plant extracts in these products also possess anticancer activities, which can help eliminate cancer cells that dislodged upon needle puncture. For example, extracts from green tea, Reishi, agrimony, ginseng and curcumin have been found to trigger apoptotic cell death and inhibit growth signalling pathways in cancer cells.

Tissue-specific support: The prostate and breast are hormone-sensitive tissues, which require proper hormonal signalling to maintain optimal function. ProstaSol combines 10 plant extracts to support prostate health by modulating androgen (male sex hormone) signalling, reducing inflammation and fortifying tissue integrity. Indole-3-carbinol, a compound found in cruciferous vegetables, helps balance oestrogen metabolism and detoxifies harmful molecules. These bioprotective properties support the prostate or breast tissue locally, helping them to recover better from biopsy trauma.

This protocol is also optimised for strategic timing: starting 10 days before the biopsy allows immune activity to ramp up and galectin-3 levels to drop by the time of the biopsy procedure. Continuing for 30 days after the biopsy ensures protection through the wound-healing phases and when the risk of tumour cell seeding or dissemination peaks. So, by targeting the vulnerabilities created by biopsy, this protocol offers a proactive, multi-layered defence to minimise the risk of dislodged tumour cells colonising other tissues.

Figure 4. Bacterial DNA damage by colibactin is more common in early-onset colorectal cancer and strikes key cancer genes. (A, B) Distinctive DNA scars left by colibactin (SBS88 and ID18) are far more frequent in colorectal cancers diagnosed before age 40, and decline steadily with increasing age. (C, D) These bacterial scars can directly cause mutations in critical genes like APC, which normally prevents tumour growth. In some cases, colibactin was responsible for a large fraction of early APC driver mutations, helping explain how childhood exposure to these gut bacteria could set cancer in motion decades before diagnosis. Source: adapted from Díaz-Gay et al. (2025), Nature.

Conclusion

Biopsies remain essential for cancer diagnosis, but the accumulating evidence shows they are not biologically harmless procedures. By acknowledging the rare but real risks of tumour cell seeding and dissemination, we open the door to safer diagnostic practices without compromising accuracy or delaying care. The biopsy protection protocol offers a science-backed, non-invasive strategy to support the body before and after biopsy by reducing cell injury-associated inflammation and oxidative stress, enhancing immune defences, blocking early metastatic steps, eliminating dislodged cancer cells, and providing breast- or prostate-specific protection. Until medicine can guarantee that biopsies do no harm, this protocol serves as a multi-layered defence against moments of vulnerabilities. When risks are invisible and difficult to measure, taking precautionary steps becomes not just prudent but necessary.