At just 26 years old, Courtney Bailey from England noticed an unusual bloody discharge from her nipple. Doctors initially dismissed it as a hormonal imbalance, believing she was too young for breast cancer. However, a precautionary biopsy later confirmed the presence of breast cancer. Further testing revealed precancerous cells beyond the milk ducts, suggesting a high risk of cancer progression. In 2024, Bailey made the difficult decision to undergo a mastectomy, the surgical removal of a breast. Now, at an age when most young women are focused on careers and relationships, Bailey faces life with one breast missing – an unsettling reminder that breast cancer is not always a disease of older women.

Bailey’s story highlights a disturbing trend: breast cancer diagnoses are rising among young women worldwide. While increased screening has led to more early cancer detections, it does not fully explain this trend. Routine mammography screening typically begins at age 50, with some recent guidelines lowering the recommendation to age 40. However, most young women with early-onset breast cancer still fall outside these screening programs.

The latest 2024 report from the American Cancer Society (ACS) further underscores this trend. Using high-quality statistical data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the ACS documented that breast cancer incidence is increasing by 1% annually, even as breast cancer deaths have declined by 10% over the past decade. More concerningly, cases among women under 50 are rising at 1.4% per year, which is a rate 40% higher than the overall incidence increase.

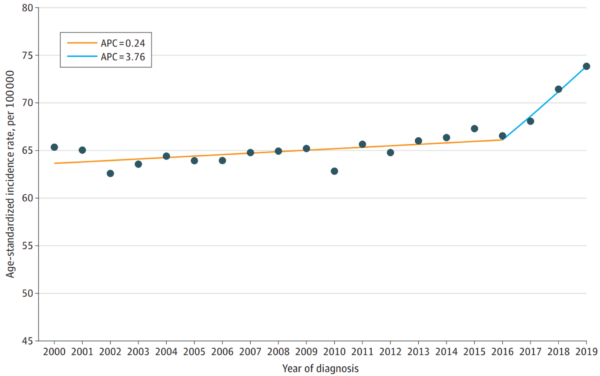

These findings align with a 2024 study from the Washington University School of Medicine, which analysed data from over 217,000 U.S. women diagnosed with breast cancer between 2000 and 2019 to examine the incidence pattern of early-onset, aggressive cases. In 2000, the incidence of invasive breast cancer among women under 50 years old was only 64 cases per 100,000 individuals. For the next 16 years, the increase was slow and steady, at just 0.24% per year. After 2016, however, the trend took a sudden and unexplained turn, with incidence rates accelerating at 3.76% per year. By 2019, the rate had climbed to 74 cases per 100,000 individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The overall incidence of invasive breast cancer among U.S. women aged 20 to 49 years from 2000 to 2019. In 2016, the incidence took a sharp turn towards a drastic increase. Note: APC denotes annual percent changes. Source: Xu et al. (2025), JAMA Network Open.

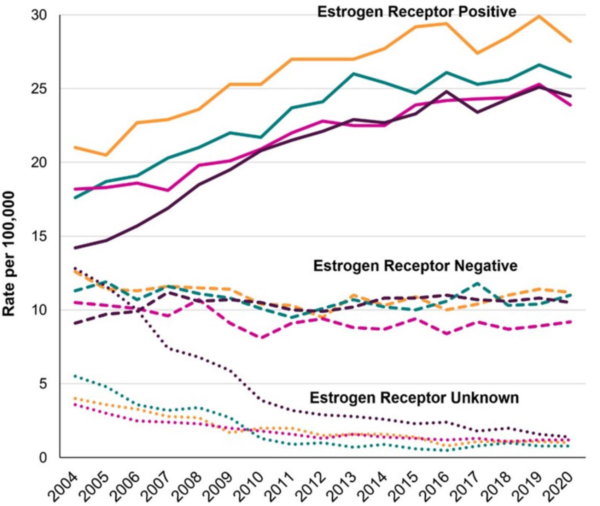

Interestingly, the rise in early-onset breast cancer is primarily driven by hormone receptor-positive tumours, while hormone receptor-negative cases are either declining or stabilising (Figure 2). Hormone receptor status refers to whether a breast tumour has oestrogen and/or progesterone receptors, which enable cancer cells to bind hormones that can stimulate growth. As hormone receptor-positive breast cancer relies on hormones like oestrogen and progesterone to grow, it can be treated with hormonal therapies that block or suppress these hormones. This shift further suggests that lifestyle and environmental factors influencing the hormonal balance in younger women may be driving the surge in early-onset breast cancer.

Globally, early-onset breast cancer is rising at a faster rate than other types of early-onset cancers. A 2023 study analysed the incidence of 29 early-onset cancers from 204 countries from the Global Burden of Disease (GDB) database, which is the most comprehensive research program measuring the global impact of diseases. The findings revealed that early-onset breast cancer had the sharpest increase in both incidence and death since 1990, surpassing all other early-onset cancers. Nasopharyngeal and prostate cancers followed in terms of incidence growth, while lung, stomach and colorectal cancers had the next highest increases in death rates. Notably, the rise in early-onset breast cancer incidence was most pronounced in high-income countries, whereas the rise in death was more severe in low- and middle-income countries. This contrast may be due to high-income countries benefiting from earlier detection and more advanced treatments, leading to lower death rates.

More concerningly, early-onset breast cancer tends to be more aggressive and associated with poorer survival outcomes compared to older, post-menopausal breast cancer. Studies have found that younger, pre-menopausal women are more likely to develop larger and more advanced tumours. These tumours also often exhibit higher expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), which promotes rapid tumour growth and proliferation. As a result, early-onset breast cancer carries a greater risk of metastasis (cancer spread) and mortality (death). Given the sharp rise in cases of early-onset breast cancer worldwide, there is an urgent need to understand the underlying factors fuelling this alarming trend.

Figure 2. Incidence rates of early-onset breast cancer (diagnosed between 25 to 39 years) by oestrogen receptor status in the U.S. from 2004 to 2020. Source: Kehm et al. (2025), Cancer Causes and Control.

While genetic predisposition is an important risk factor for breast cancer, it cannot fully explain the increasing incidence of breast cancer among young women. In fact, only 5-10% of all breast cancers are linked to inherited genetic mutations. The majority of young women diagnosed with breast cancer have no known genetic predisposition. Additionally, genetic changes occur gradually over generations, whereas the surge in early-onset breast cancer has occurred within just a few decades – too fast to be driven by inherited genetic changes alone. This suggests that environmental and lifestyle risk factors may be triggering cancer in genetically susceptible individuals or even driving new mutations in those with no family history of the disease.

Fortunately, the abovementioned 2023 study on the Global Disease Burden (GDB) database also explored the risk factors of early-onset breast cancer. Alcohol consumption, tobacco use, dietary factors, physical inactivity and metabolic imbalances were identified as key contributors to the increasing burden of early-onset breast cancer. Such burden was measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), the total of years of life lost due to early death and years lived with illness or disability. Essentially, DALYs reflect how much a disease impacts lifespan and quality of life. The DALYs contributions of the individual risk factors for early-onset breast cancer are as follows:

- Alcohol consumption: 4.5%

- Tobacco smoking: 4.4%

- Diet high in red meat: 2.9%

- High levels of fasting blood glucose: 2.6%

- Physical inactivity: 0.6%

Alcohol use was the leading risk factor, accounting for 4.5% of DALYs linked to early-onset breast cancer, followed by tobacco smoking, dietary factors, high fasting blood glucose levels and physical inactivity. However, totalling these risk factors amounts to only 15% of the total DALYs, indicating that the remaining 85% comes from other contributors, such as hormonal imbalances, environmental exposures and other unmeasured factors.

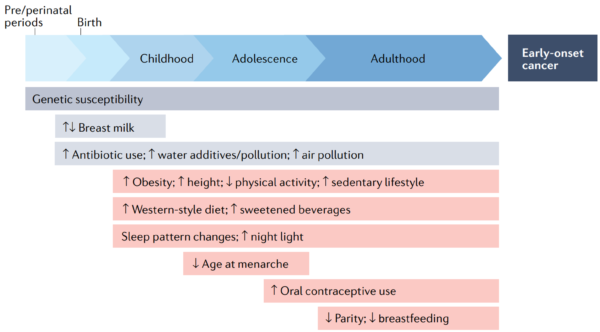

Following this, a 2022 comprehensive review by scientists at the Harvard Medical School, U.S., pointed out that drastic changes in lifestyle and environmental exposures over the past decades could be driving the rise in early-onset cancers. Factors like metabolic syndrome, physical inactivity, tobacco smoke exposure, and consumption of processed foods and alcohol have become more prevalent. Disrupted circadian rhythm (e.g., night shift work and sleep deprivation) and womb conditions (e.g., maternal smoking and diet) may also have long-term effects on cancer risk. The review also emphasised that changes in reproductive patterns affect the risk of early-onset breast cancer. Earlier menstruation, fewer pregnancies and delayed childbirth prolong a woman’s lifetime exposure to oestrogen and progesterone, which may elevate the risk of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Without the natural breaks from pregnancy and breastfeeding, these hormones remain active for longer periods, extending the window of hormonal influence that could drive cancer development (Figure 3). As more young women choose to delay or forgo motherhood, especially in developed countries, this cultural shift may be further contributing to the growing incidence of early-onset breast cancer.

Figure 3. How life experiences and exposures may contribute to early-onset cancer. From the moment of conception, a person is exposed to various factors that may influence cancer risk. As cancer often takes years or even decades to develop, exposures during early life can influence the development of cancers that appear before age 50. Source: Ugai et al. (2022), Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology.

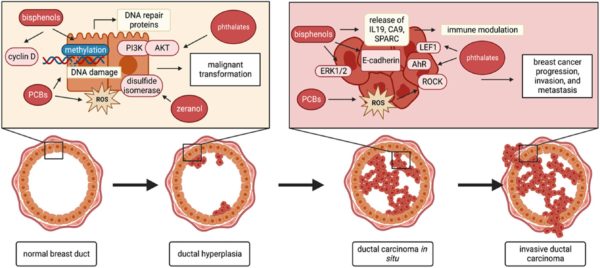

Moving on, some scientists warn that younger individuals are exposed to high levels of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), such as bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates, commonly found in plastics, household products and cosmetics. These EDCs can interfere with the body’s natural hormonal signals and promote cellular pathways favourable for carcinogenesis (Figure 4). A 2024 study has identified over 900 breast cancer-related chemicals shown to either induce breast cancer in animals or disrupt hormonal functions in cells. Alarmingly, nearly half of these chemicals are found in plastics, underscoring growing concerns about how plastic pollution may contribute to the increasing breast cancer rates among the younger population.

Emerging research suggests that long-term exposure to these chemicals, especially during critical periods of breast development – such as puberty and early adulthood – may play a role in the development of hormone-positive breast cancer. Some researchers further highlight the ‘cocktail effect,’ where prolonged exposure to multiple EDCs, even at low doses, may collectively disrupt hormone-sensitive pathways that individual chemicals might not. As daily exposure to EDCs is nearly unavoidable due to their widespread presence in food, water and the environment, this raises concerns about their cumulative impact on the body over time, potentially increasing breast cancer risk in ways that remain poorly understood.

These risk factors together help explain why a seemingly healthy young woman may develop breast cancer. Many young women diagnosed with the disease do not fit the traditional high-risk profile as they maintain a healthy weight, exercise regularly and follow a balanced diet. While these habits are crucial for overall well-being, they do not provide absolute protection against breast cancer. Instead, early-onset breast cancer likely arises from a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, hidden environmental exposures and subtle biological changes that build up over time. This makes it challenging to predict who will be affected by early-onset breast cancer, even among those who appear to be in optimal health.

Figure 4. How endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) may contribute to the development and progression of breast cancer. EDCs can interfere with the cell signalling pathways at multiple stages of breast cancer, from its initial formation to its progression and spread (metastasis). Abbreviations/acronyms: AhR, aryl-hydrocarbon receptor; AKT, protein kinase B; ERK 1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; IL-19, interleukin 19; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyls; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinases; ROS, reactive oxygen species. Source: Winz et al. (2023), Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology.

With early-onset breast cancer cases on the rise, addressing this health crisis requires a collective and multifaceted approach. While some risk factors like genetic predisposition cannot be changed, many environmental, hormonal and lifestyle-related influences are modifiable. Current evidence suggests that the key to curbing the burden of early-onset breast cancer lies in prevention, early detection, stronger regulatory policies and further research:

- Rethinking breast cancer screening: Routine mammography starts at 40 or 50, yet breast cancer rates are rising in younger women. Universal screening is impractical due to the high risk of false positives, but risk-based screening – targeting women with family history, hormone exposure or lifestyle risk – could enable earlier detection. Emerging medical technologies such as liquid biopsies and urine cancer tests may also aid early detection efforts in a non-invasive and more cost-effective manner.

- Reducing exposure to environmental risk factors: Stronger regulations are needed to limit BPA, phthalates and other EDCs, especially in food and water contact materials. At an individual level, women can take proactive steps to reduce exposure, such as using glass or stainless-steel containers, avoiding plastic-packaged foods, choosing EDC-free cosmetics and filtering drinking water.

- Prioritising a healthy lifestyle: While maintaining a healthy weight, exercising and eating a balanced diet are crucial, addressing other risk factors is equally important, such as limiting alcohol intake, avoiding tobacco exposure and managing a proper circadian rhythm (e.g., reducing night shift work and artificial light exposure).

- Raising awareness and advocacy: Many young women often face medical dismissal by being told they are too young for breast cancer. Education campaigns for women and healthcare providers can improve awareness of early warning signs. Women with multiple risk factors should feel empowered to advocate for their own health and request screenings if they experience persistent breast-related symptoms.

- The need for more research: Despite the alarming increase in early-onset breast cancer, research into its causes remains limited. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the impact of reproductive changes, metabolic imbalances and other risk factors like EDCs on early-onset breast cancer. More research should also be conducted on preventive measures, including EDC-free products, lifestyle modifications and even the potential role of phytotherapy.

Phytotherapy refers to the use of plant-based compounds for health and medical purposes. While more research is needed, several plant compounds have already shown promising effects in targeting pathways linked to breast cancer development, particularly hormone receptor-positive types. For instance, isoflavones (found in soy) and lignans (found in flaxseeds) can act as phytoestrogens in the body. By binding to oestrogen receptors, phytoestrogens help regulate hormone levels by competing with and reducing the effects of natural and synthetic oestrogens, which may fuel hormone-positive breast cancer.

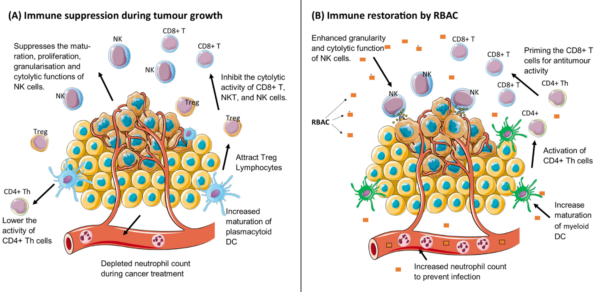

Other plant compounds such as curcumin (from turmeric), quercetin (apples, onions or berries), epigallocatechin-3-gallate (green tea), resveratrol (grapes and red wine), indole-3-carbinol (cruciferous vegetables) and arabinoxylan (rice brain) are well-known for their antioxidant, immunomodulatory and anticancer properties (Figure 5). Large cohort studies have reported that frequent intake of these plant compounds helps reduce the risk of breast cancer and other diseases. Therefore, phytotherapy can be a complementary approach to support overall health, regulate hormones and potentially lower the risk of breast cancer.

Figure 5. Rice bran arabinoxylan compound (RBAC) supports the immune system of cancer patients. (A) Cancer weakens the immune system by suppressing anti-tumour immune responses. (B) RBAC counteracts this suppression by boosting the immune activities of natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DC), regulatory T-cells (CD4+) and killer T cells (CD8+). RBAC also helps restore the levels of immune cells in patients with low white blood cell counts (neutropenia). Source: Ooi et al. (2024), Pharmaceutical Biology.

The increasing incidence of early-onset breast cancer is not just a statistic. It is altering the lives of young women who never expected to face this disease. It is a warning that something in our environment, lifestyle or culture is accelerating the disease risk in young women. While genetics play a role, they do not explain the sudden surge seen in just a few decades. The challenge now is not just treating cancer but rethinking prevention approaches by improving risk-based screening, demanding stronger regulations on potentially harmful chemicals, and investing in research into why this is happening in the first place.

On an individual level, women can take proactive steps to minimise their risk. A healthy lifestyle should be prioritised, such as avoiding tobacco, alcohol and processed foods, staying physically active, maintaining a stable circadian rhythm, and minimising exposure to EDCs. Additionally, reproductive choices such as earlier pregnancy (if planned) and breastfeeding may offer protective benefits. Women may also consider embracing phytotherapy for added protection in supporting hormonal and immune health. The fight against breast cancer begins long before a tumour is detected; it starts with the choices we make today.