Every breast cancer survivor lives with an invisible uncertainty: the possibility that somewhere, a few dormant disseminated tumour cells (DTCs) escaped cancer therapy and lie hidden in distant tissues like the bone marrow. These cells can remain silent for years or even decades, waiting for the right conditions, such as a weakened immune system, to reawaken and cause metastatic cancer recurrence. But what if we could find these cells, weaken them and clear them before they ever re-emerge? A remarkable new clinical trial, published in the prestigious Nature Medicine journal, has taken the first real step toward that vision.

The Problem with Disseminated Cancer Cells (DTCs)

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of death among women, claiming about 685,000 lives globally every year. Most women are diagnosed with early-stage disease, which is, in principle, curable. Yet an estimated 20–30% of them will still experience a metastatic cancer recurrence more than ten years later, driven by dormant DTCs that survived initial therapy, a phenomenon known as minimal residual disease (MRD). Common needle biopsy procedures used to diagnose cancers also carry a small risk of dislodging tumour cells as the needle penetrates the tumour, which may allow a few cells to escape and become DTCs.

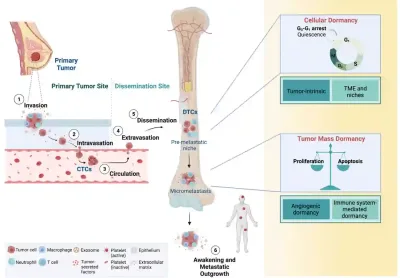

These DTCs are cancer cells that break away from the original tumour and disseminate (travel) to other parts of the body, most often in the bone marrow or lymph nodes (Figure 1). They can lie completely dormant (inactive) for years or even decades, not dividing, not forming detectable tumours and not causing any symptoms. Because they are rare and inactive, current medical scans and routine blood tests usually cannot detect them. Under the right conditions, such as a weakened immune system or changes in the tissue environment, these dormant cells can “wake up,” begin to grow again and seed metastatic cancer. At this stage, the cancer is generally incurable, with therapies focusing on controlling the disease and prolonging life.

Clinical studies that sampled bone marrow in women with breast cancer showed that dormant DTCs are present in around one-third of patients, even after they have completed surgery, chemotherapy or other standard cancer therapy. Finding even a single DTC is far from trivial. Women with as little as ≥1 DTC in their bone marrow have a two- to threefold higher risk of metastatic cancer relapse and death compared with women whose bone marrow is completely clear. Crucially, DTC status predicted clinical outcomes independently of traditional risk factors – such as tumour size, hormone receptor status or lymph node metastasis – emphasising DTCs as a strong biological warning sign for metastatic recurrence.

Figure 1. A few breast cancer cells can escape the original tumour, enter the bloodstream and travel to distant organs such as the bone marrow. Once they settle there, these disseminated tumour cells (DTCs) can switch into a dormant or inactive state. However, under the right conditions, these DTCs can reawaken and grow into metastatic tumours. Source: Ring et al. (2022), Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology.

Although adjuvant (additional) chemotherapy and hormonal therapy can lower recurrence risk by eliminating residual DTCs, they come at a cost. Many breast cancer survivors who would never have relapsed are exposed to intensive therapies they did not need. These therapies also pose substantial short-term (e.g., low blood counts, vomiting and hair loss) and long-term (e.g., neuropathy, chronic fatigue and secondary cancers) health burdens. Such challenges highlight a critical gap in modern oncology: the need to (1) identify which patients harbour dormant DTCs, (2) develop therapies that target these dormant DTCs, and (3) demonstrate that clearing or depleting them reduces the risk of metastatic recurrence.

The Breakthrough CLEVER Clinical Trial

While the biology of dormant DTCs has intrigued researchers for years, until now, no clinical trial in breast cancer survivors has directly enrolled DTC-positive individuals and applied therapies designed to deplete those DTCs. To this end, oncologists at the University of Pennsylvania, USA, conducted the CLEVER (hydroxyCLoroquine and EVErolimus for Recurrence prevention) clinical trial to show, for the first time, that such DTCs can be targeted and sustainably reduced in breast cancer survivors.

The choice of drugs, hydroxychloroquine and everolimus, did not come out of thin air. It was grounded in years of preclinical work using mouse models that mimic human breast cancer dormancy and recurrence. In these models, residual DTCs that survive cancer therapy switch into a dormant state characterised by two key changes: suppressed mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling and upregulated autophagy, a self-cleaning process that helps stressed cells survive. When researchers blocked autophagy in these DTCs using chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, they saw fewer DTCs and better recurrence-free survival. Inhibiting mTOR with rapamycin or everolimus also reduced DTC burden and cancer recurrences.

As chloroquine and rapamycin are not ideal for long-term use in otherwise healthy survivors, the team chose their more clinically “user-friendly” cousins: Hydroxychloroquine, a better-tolerated autophagy inhibitor used to treat autoimmune diseases, and everolimus, an oral mTOR inhibitor already approved for treating advanced breast cancer, with a known safety profile in this population. Together, hydroxychloroquine and everolimus offered a practical way to hit both survival pathways that help dormant DTCs survive and persist.

To translate these findings into humans, the investigators ran a randomised phase 2 clinical trial in breast cancer survivors within five years of diagnosis who had no clinical evidence of metastasis but at least one DTC detected in their bone marrow. Bone marrow aspiration was conducted in 184 survivors, of whom 55 (28%) were DTC-positive and randomised into one of the four groups:

- Hydroxychloroquine alone: 600 mg orally twice daily for 6 months.

- Everolimus alone: 10 mg orally once daily for 6 months.

- Combined hydroxychloroquine and everolimus for 6 months.

- 3-month observation period (a no-treatment comparator), followed by combined hydroxychloroquine and everolimus for 6 months.

The primary endpoint of this clinical trial was feasibility or safety: Can over 70% of survivors complete the treatment without serious toxicity? After all, there is little meaning if the treatment is efficacious but unsafe, where the risks outweigh the benefits. Fortunately, all treatment regimens met the feasibility criterion, where nearly all survivors completed treatment with hydroxychloroquine and/or everolimus without severe toxicity. Side effects were mostly mild and expected (e.g., gastrointestinal upset or rashes).

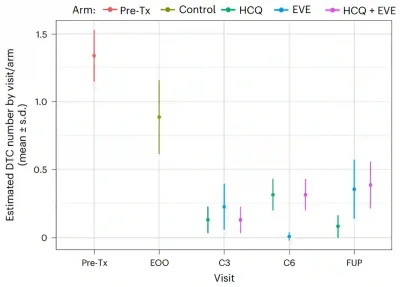

The secondary endpoints measured treatment efficacy: Can these drugs actually shrink the pool of dormant DTCs and prevent cancer recurrence? For reducing DTCs, the answer was a strong yes. After only three months of treatment, hydroxychloroquine, everolimus and their combination lowered DTC counts by about 80%, 78% and 87%, respectively, compared with observation (no treatment). These reductions were also sustained for more than three years, indicating that the treatment can sustainably shrink the reservoir of dormant DTCs (Figure 1).

Figure 2. The number of dormant disseminated tumour cells (DTCs) in the bone marrow over time in each treatment group. Before treatment (pre-tx), patients had detectable DTCs. After a 3-month observation without treatment (end of observation, EOO), the numbers dropped only slightly. In contrast, after three months (3 cycles, C3) of treatment with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), everolimus (EVE) or both (HCQ + EVE), DTC levels fell sharply. These reductions were maintained at six months (6 cycles, C6) and at follow-up (FUP) more than three years later. Source: DeMichele et al. (2025), Nature Medicine.

When looking at recurrence, the findings were also promising. As everyone eventually received treatment, the trial cannot prove that these drugs prevent relapse. Even so, the 3-year recurrence-free survival looked remarkably good: 92% with hydroxychloroquine, 93% with everolimus and 100% with the combination. For comparison, women with similar high-risk features, especially those who still have residual disease or DTCs, usually have a 3-year recurrence-free survival closer to 60–80%. In that light, the CLEVER results appear better than what would normally be expected. This clinical trial, therefore, delivers the first human evidence that dormant DTCs in breast cancer survivors can be safely depleted with pharmacological agents, resulting in lower rates of metastatic cancer recurrence.

“The CLEVER trial marks a watershed moment: the first deliberate targeting of DTCs in patients, achieving measurable reductions in MRD [minimal residual disease] and early signs of clinical benefit,” stated a news feature in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. “Although confirmation in larger randomised studies is essential, these results outline a future in which breast cancer recurrence might not only be treated but prevented.”

Phytotherapy Targeting Dormant DTCs

Given the success of hydroxychloroquine and everolimus in targeting dormant DTCs through autophagy and mTOR pathways, an intriguing question is whether any natural compounds or plant extracts share similar mechanisms. This falls under the broad but untapped field of phytotherapy, the use of plant compounds for therapeutic purposes.

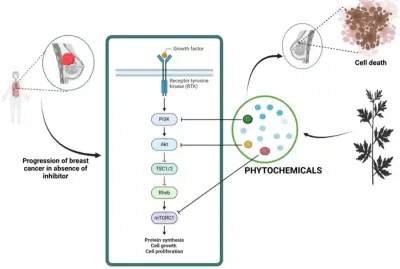

Dormant DTCs depend on autophagy for survival and recurrence, and blocking this process undermines their ability to re-emerge. The CLEVER clinical trial builds on this rationale: dormant DTCs show elevated autophagy and low mTOR signalling, with hydroxychloroquine inhibiting autophagy and everolimus further constraining mTOR activity. Hence, any phytotherapy candidates would be those that mirror these mechanisms by either inhibiting autophagy or mTOR signalling in DTCs or similarly resistant cancer cell populations.

For example, withaferin A (from ashwagandha) has been shown to disrupt lysosomal function and block autophagy in human breast cancer cells. This means the cancer cells can no longer use their lysosomes to break down and recycle damaged components for fuel. As their ability to generate energy collapses, the cells become depleted of essential energy sources and ultimately undergo apoptotic cell death. Likewise, green tea polyphenols can block the protective autophagy that cancer cells initiate as a survival response to chemotherapy. By shutting down this autophagic escape pathway, these polyphenols re-sensitised cancer cells to being killed by chemotherapy. In parallel, plant compounds such as curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate and quercetin have been found to downregulate mTOR signalling in breast cancer cells, thereby inhibiting cancer cell survival, proliferation and metastasis (Figure 3).

Figure 3. How plant compounds can help shut down cancer-promoting signals. In breast cancer, growth signals activate a chain of proteins (PI3K → Akt → mTOR) that drive tumour cell growth and survival. Certain plant-derived compounds (phytochemicals) can interfere with different steps along this pathway, weakening the signals cancer cells rely on. Source: Wali et al. (2025), Nutrition and Cancer.

Furthermore, other plant compounds have exhibited the capacity to inhibit DTCs or circulating tumour cells (CTCs) via mechanisms other than autophagy or mTOR suppression:

- Curcumin (from turmeric): Curcumin has been shown in several cancer models to make it harder for CTCs to survive and form new tumours. It reduced the number of CTCs in the bloodstream, weakened their ability to stick to blood vessel walls and prevented them from anchoring in distant organs to form DTCs.

- Quercetin (found in onions, apples and berries): Quercetin interferes with the signals that help cancer cells spread. It can block communication between tumour cells and blood vessel cells, reduce the release of pro-metastatic growth signals and lower the number of aggressive CTCs in the blood.

- Glycyrrhizic acid (from liquorice root): This compound acts like a decoy that prevents CTCs from binding to the E-selectin receptor on blood vessel walls – a key step cancer cells use to exit the bloodstream and settle in distant tissues as DTCs.

Collectively, these studies suggest that certain plant-derived compounds can interfere with key steps in the metastatic cascade, even if they have not yet been tested directly in dormant bone marrow DTCs. While such data are still preclinical, they offer mechanistic evidence that phytotherapy could one day complement pharmacological approaches to target minimal residual disease and prevent metastatic cancer recurrence. In the end, the future of breast cancer care may not rely on finding new tumours but on outsmarting the cells that never fully left.