Background

Cancer, often perceived as a formidable disease, is treatable in its early stages, emphasising the importance of early diagnoses. Traditionally, tissue biopsies have been the gold standard for diagnosing cancer. However, they carry risks due to their invasive nature, such as pain, infections, and the potential dislodgement of cancer cells from the tumour during the needle biopsy process. Recent advancements have highlighted the benefits of a less invasive option: liquid biopsy, which detects cancer cells and DNA that escape from tumours into the bloodstream.

Integrative Cancer Care has previously covered the revolutionary impact of blood-based liquid biopsy in advancing early cancer detection and ongoing monitoring. In this article, we shift our focus to a lesser-known yet equally promising method: the urine-based liquid biopsy. This concept emerged from the discovery that trace amounts of cancer cells can be detected in urine samples. Adding to the intrigue, studies show that trained dogs can ‘sniff out’ bladder and prostate cancer from urine samples (Figure 1). These findings underscore the potential of urine as a viable source for early cancer detection, broadening the scope of liquid biopsy applications.

Figure 1. Stewie, a 10-year-old Australian Shepherd, has been sniffing urine samples for cancer in the laboratory since she was 8 years old. Source: Robins (2024), American Kennel Club.

Principles of Urine Biomarkers

Contrary to the idea of ‘waste,’ urine is an invaluable biofluid routinely used in standard medical tests to help diagnose conditions such as kidney disease, diabetes, and urinary tract infections. The main advantage of urine testing lies in its non-invasive collection method, which can be done independently and painlessly, ensuring higher patient acceptance. This makes urine tests particularly suitable for regular, long-term monitoring and screening, which are key strategies for catching cancer in its earliest and most treatable stages.

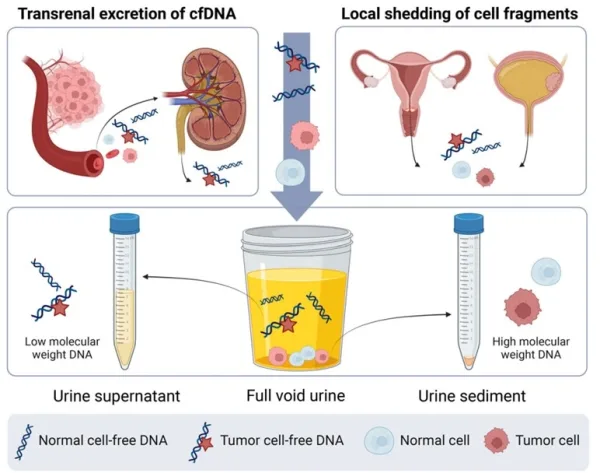

As cancer cells grow or die, they release DNA fragments and other cellular components into the bloodstream. These components are then filtered by the kidneys, with smaller molecules passing into the urine via a process known as transrenal excretion. Moreover, tumours of the urogenital tract can directly shed cellular fragments into the urine. As a result of these mechanisms, two types of tumour DNA are present in urine: (i) low molecular weight DNA from transrenal excretion, and (ii) high molecular weight DNA from the local shedding of cellular fragments. Due to the differences in molecular weight, the former accumulates in the urine supernatant (top part), while the latter settles in the urine sediment (bottom part) (Figure 2).

Analysing these markers in urine allows clinicians to detect and monitor cancers non-invasively, leveraging the body’s natural waste filtration system to provide diagnostic insights. For instance, urine sediment has been identified as particularly effective for detecting bladder and cervical cancers due to its high concentration of exfoliated cancer cells. Conversely, urine supernatant is more effective for detecting cancer outside of the urogenigal tract because it is rich in cell-free DNA, which carries genetic mutations and epigenetic patterns indicative of cancer.

Figure 2. Urine as a liquid biopsy for cancer detection. Urine contains various components, including cell-free DNA and cellular debris. Cell-free DNA enters the urine through transrenal excretion, while the anatomical positions of the urogenital organs facilitate the local shedding of cells and DNA into the urine. Source: Wever and Steenbergen (2024), Molecular Oncology.

Current Applications

Urine tests have been primarily explored in urogenital cancers, particularly bladder and prostate cancers. Currently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved multiple urine tests for the detection and monitoring of bladder cancer, and only one for prostate cancer.

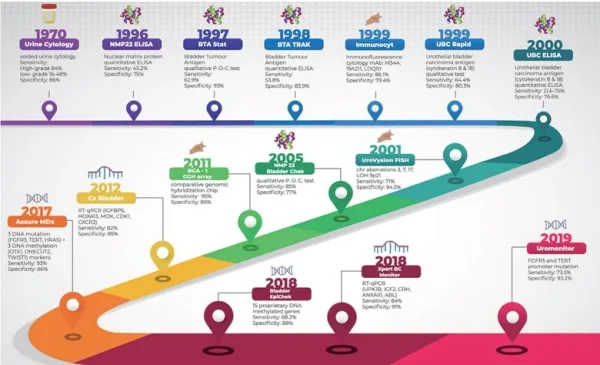

An example of a bladder cancer urine test is BladderChek, which detects the presence of nuclear matrix protein 22 (NMP22) in the urine. NMP22 is part of the cellular nuclear matrix, which breaks down more frequently in bladder cancer cells due to their higher metabolic rate, resulting in more NMP22 being released into the urine. Other FDA-approved urine tests for bladder cancer include (i) UroVysion, which detects chromosomal abnormalities; (ii) ImmunoCyt, which detects cancer-specific antigens; and (iii) Uromonitor, which detects certain gene mutations (Figure 3).

However, these tests are still limited by their high rates of false positives (i.e., detecting cancer when it is absent), ranging from 10-20%. As a result, such urine tests are typically used when cystoscopy findings are inconclusive. Cystoscopy involves inserting a camera into the urethra, which is the standard method for diagnosing bladder cancer. However, cystoscopy is invasive, costly and carries risks of pain and infections. This warrants the development of non-invasive alternatives, with urine cancer tests making significant strides towards bridging this clinical gap. For instance, a 2023 clinical trial demonstrated that the Uromonitor urine test for bladder cancer could have prevented 42% of unnecessary cystoscopy procedures.

Figure 3. Timeline of the various urine cancer tests for bladder cancer that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved, with their respective sensitivity and specificity scores. Source: Humayun-Zakaria et al. (2021), Translational Andrology and Urology.

For prostate cancer, Progensa PCA3 is the only FDA-approved urine cancer test. This diagnostic test detects the expression of the PCA3 gene in urine samples, which is overexpressed in prostate cancer cells by up to 100-fold compared to normal prostate cells. The Progensa PCA3 test has been useful in selecting patients who are more likely to benefit from a tissue biopsy, thus reducing unnecessary procedures and risks. Clinical trials have shown that Progensa PCA3 urine tests could prevent up to 70% of avoidable tissue biopsies for prostate cancer without compromising early detection.

While tissue biopsy remains the standard diagnostic method for most cancers, it is invasive, similar to a minor surgery. More concerning is that the procedure involves directly penetrating the tumour, which can sometimes dislodge cancer cells. This dislodgement poses a small risk of seeding secondary cancers elsewhere in the body. Given these risks, tissue biopsies should be conducted sparingly. As non-invasive urine cancer test technology continues to improve, it may help transform cancer diagnostics, decreasing the need for frequent tissue biopsies.

More recently, interest in urine tests has been expanding to cancers beyond the urogenital tract, including breast, lung and colorectal cancers. Efforts are also being made to standardise sampling handling and analytical methods of urine cancer tests, as well as to improve their accuracy. For example, a new study introduced MyProstateScore, a urine test that detects 18 different genes related to prostate cancer. This test has demonstrated an impressive accuracy of 95-99% in clinical settings, a feat not seen with previous urine cancer tests.

Since the kidneys filter out metabolites and other waste products from the bloodstream, biomarkers from any cancer present in the blood can theoretically appear in the urine. Therefore, researchers are pursuing the development of pan-cancer diagnostics based on blood or urine. For instance, scientists at the US Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have innovated a paper strip urine tests capable of detecting up to 46 different cancer biomarkers on a single strip. Although this technology has yet to undergo rigorous clinical trials, it represents a significant shift towards making early cancer detection more convenient and accessible.

“We are trying to innovate in a context of making technology available to low- and middle-resource settings,” Professor Sangeeta Bhatia, MD, PhD, a biological engineer at MIT, said in a press release. “Putting this diagnostic on paper is part of our goal of democratising diagnostics and creating inexpensive technologies that can give you a fast answer at the point of care.”

At present, urine cancer tests help enhance cancer diagnostic protocols by reducing the need for invasive tissue biopsies. With further research and refinement, urine cancer tests also strive to make early cancer detection widely accessible by capitalising on the non-invasive method of urine collection. Envision a future where detecting cancer could be as straightforward and routine as taking an over-the-counter pregnancy test. This would transform the daunting prospect of cancer diagnosis into a manageable part of regular health maintenance.